Every one of us knows the tragic tale of the Titanic. It has been made into a blockbuster film, with a similarly famous theme song, and helped launch Leonardo DiCaprio as a heart-throb (and an almost-oscar-winner meme… until recently). The Titanic certainly was a horrendous disaster, in many ways, and it will probably remain in our public consciousness as one of the most infamous disasters of all time for a long time to come. But on the night of the 25th November, 1120, a similar tragedy struck in the English Channel that had catastrophic consequences across Western Europe that we couldn’t begin to equate to modern terms.

In 1120, King Henry I was King of England, and Duke of Normandy. As a result, Henry split his time between England and his lands in France. In November 1120, he and many of his court had been in Normandy, attending to business. The time soon came to return to England, and all of his retinue with him. A man named Thomas FitzStephen was captain of a ship called the White Ship – Thomas’ father, Stephen FitzAirard, had been captain of the ship the Mora, which had been William the Conqueror’s flagship during his invasion and conquest of England in 1066. As a result of this pre-eminence, Thomas offered the use of his ship to Henry I to use to make the voyage back from Barfleur to England. Henry had already planned to use a different ship, but as a gesture towards Thomas, he allowed many of his retinue to sail on the White Ship, including his only male heir, William Adelin, two of his illegitimate children, and many other nobles from both England and France.

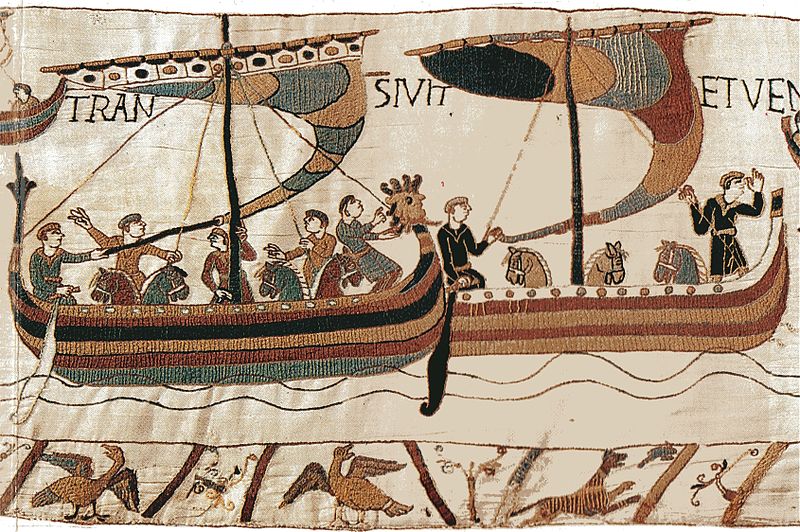

William’s invasion fleet, from the Bayeux Tapestry.

There were probably around 300 people on the ship as it was ready to depart; Prince William seems to have given orders for an abundance of wine to be delivered amongst both crew and passengers, and many of the young nobles took advantage of this rare opportunity of separation from their parents and the strict King to party as much as they could. Those on board had been drinking so heavily that some passengers even disembarked before the ship set sail, “observing that it was overcrowded with riotous and headstrong youths”. One such person was Stephen of Blois, future King of England, who said he was too sick to make the trip. As the vessel was about to depart, some priests came with holy water to bless the ship for its journey, but the passengers drove them away, laughing at them. The crew of the ship included fifty experienced rowers, and an armed marine force, who shooed the rowers away from their benches and took over.

Henry’s ship and the royal fleet had already set sail from Normandy, and the drunken revellers aboard the White Ship urged Thomas and his crew to overtake the royal fleet. Thomas, who was also drunk, and confident in his skill and the skill of his crew, boasted that it would be easy to do so, and gave the signal for the ship to depart. The ship raced out of the harbour, and the starboard bow of the White Ship crashed into a huge rock sticking out of the water. The ship very quickly filled with water, drowning everyone on board apart from two souls. These two men managed to cling onto part of the ship through the night in the cold water until they were rescued. One man was a butcher, the other a young nobleman.

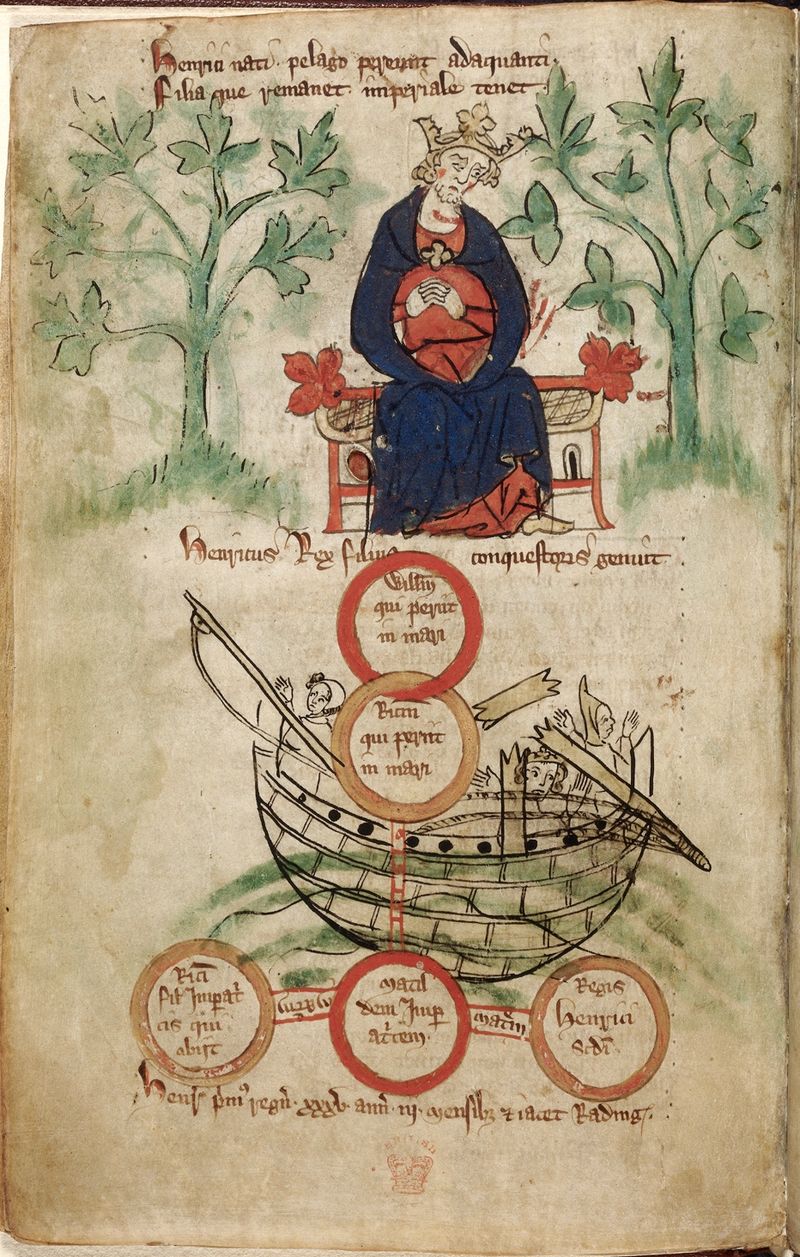

The sinking of the White Ship, depicted in a manuscript from c. 1320, British Library, Cotton Claudius D. ii, fol. 45v.

It was said by Orderic Vitalis, who records the episode in his chronicle, that at one point Captain Thomas surfaced from the sunken vessel, and, spotting the two men clinging to life, shouted “What has become of the king’s son?”. The men replied that “he and all who were with him had perished”. Thomas replied: “Then… it is misery for me to live any longer” and sunk beneath the waves, preferring death to facing the wrath of King Henry. Eventually, the young nobleman succumbed to cold and plunged under the waves. The butcher, however, was wearing a sheep-skin dress which kept him just about warm enough to survive until the next morning, where he was rescued by three fishermen. Those still on the shore, and those on the boats in the King’s fleet could hear the cries and screams of distress from the shipwrecked people, but were powerless to help until the next day.

The news soon spread, and the nobles of both lands wept and grieved, but no one was brave enough to tell the King the fate of his children, particularly his sole heir. William was only seventeen at the time. William initially appears to have managed to escape to a rowboat, and could have survived, but heard the cries for help of his half-sister, Countess Matilda, so turned back to rescue her. This then caused his boat to become swamped by others trying to climb in and save themselves, and they all drowned after the boat sank.

King Henry I and the sinking White Ship, c. 1307-1327, British Library, Royal MS 20 A.ii, fol. 6v.

The impact of the White Ship disaster is incredibly difficult to quantify. Between 250-300 people are believed to have died. 140 of these were knights or noblemen, and 18 were noblewomen. Servants and sailors also perished. A list compiled of those known to have died can be found on Wikipedia, here, and those who died touched royal families across Europe, including the Holy Roman Emperor. Whilst there were older nobles on board, there were many young men who were set to inherit lands and titles across England and France – including, highest of all of course, the son of the King of England and Duke of Normandy. It is difficult to imagine the impact this had on almost every family in England, France, and beyond – a whole generation of heirs were wiped out, causing immense uncertainty for many noble families.

The biggest problem, of course, impacted the throne of England. Whilst Henry had many illegitimate children, he only had two legitimate ones: his son, William, and an older daughter, Matilda. At this time, it was only conceivable that the throne of England be inherited by a man. This caused huge succession uncertainty for the country, and worry for Henry. He took a second wife, with whom he tried to produce another male heir, but the marriage remained childless. Henry was left with no choice but to proclaim his daughter, Matilda, as his sole heir. Matilda had previously been Empress of the Holy Roman Empire, but now Henry arranged for her to be married to Geoffrey of Anjou to secure the southern borders of Normandy. Henry did his best to ensure that Matilda would successfully become Queen upon his death, including making his barons both in England and Normandy swear to recognise Matilda and any future legitimate heir she might have.

Empress Matilda, from “History of England” by St. Albans monks (15th century); Cotton Nero D. VII, f.7, British Library.

After Henry’s death, this did not become a reality; Henry’s nephew, Stephen of Blois, who had so fatefully avoided embarking on the White Ship that night, seized the Crown of England from under Matilda’s feet. Matilda was not content to relinquish her birth right, and the resulting war between Stephen and Matilda has been labelled The Anarchy. It dragged from 1135 to 1153, causing devastation across England, particularly in the south. Matilda never reclaimed her throne, but after Stephen’s death, her son, Henry II, successfully became King of England. (You can read all about the Anarchy in our blog post here).

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

From this one disaster, then, came immeasurable consequences. The noble families of England and France, and even beyond, struggled to cope with the loss of so many of their children and relatives, even causing the disinherison of some families. Most importantly of all, it killed the sole male heir of the throne of England, and led to decades of uncertainty and war in England long after the fact.

I leave you with Orderic Vitalis’ summation of the impact of the disaster:

“The nobles as well as the commons lamented their superior lords, their children and kingsfolk, their acquaintance and friends; affianced damsels those to whom they were betrothed; and beloved wives their loving husbands…

What mortal tongue can fully recount the numbers of those who had to mourn this fatal disaster, or the numerous domains which were deprived of their lawful heirs, to the great detriment of many persons?”

Previous Blog Post: Fairy Tales or Medieval Reality? Historical origins of fantasy stories

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

See Orderic Vitalis, The Ecclesiastical History of England and Normandy, volume 4 (translated by Thomas Forester), pgs 33-42 for the account used here.

Other contemporary sources include William of Malmesbury, Gesta regum Anglorum, as well as: Simeon of Durham, Historia regum; Eadmer, Historia nouorum in Anglia; Henry of Huntingdon, Historia Anglorum; Hugh the Chanter, History of the Church at York; Robert of Torigni, Gesta Normannorum; Wace, Roman de Rou.

Imagine my surprise when I started scrolling through the WordPress Reader and discovered your post. You see, I had posted a piece about Henry I Beauclerc on the anniversary of his death: 1 December: https://kindredconnection.wordpress.com/2016/12/01/henry-i-beauclerc/.

Thank you for sharing this information on the White Ship tragedy and the subsequent Anarchy.

LikeLike

What a co-incidence! Your piece was very interesting, and I’m glad we could share in this interesting event

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoyed reading your posst

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike