Mermaids are creatures that appear time and again throughout history and across cultures. Typically a mermaid is portrayed as having the top half of a woman, and the bottom half of a fish, though this sometimes varies slightly. The first known stories of mermaids come from Assyria around 1000BC; the goddess Atargatis, who was the mother of the Assyrian Queen Semiramis, loved a mortal and accidentally killed him. Ashamed and distraught, Atargatis jumped into a lake and took the form of a fish, but the waters would not conceal her divine beauty. She then took the form of a mermaid – human above the waist, fish below. After the death of Alexander the Great’s sister, Thessalonike, a popular Greek legend emerged that she had turned into a mermaid. According to the legend, she would ask the sailors on any ship she would encounter only one question: “Is King Alexander alive?”. If the sailors answered “He lives and reigns and conquers the world” then she would calm the waters and bid the ship farewell. Any other answer would enrage her, and she would stir up a terrible storm, dooming the ship and every sailor on board.

The goddess Atargatis shown as a fish with human head, on an ancient Greek coin of Demetrius III Eucaerus (c. 95BC – 88BC). WikiCommons.

Elsewhere, in Norman England, a chapel built in Durham Castle around 1078 by Saxon stonemasons has what is probably the earliest surviving artistic depiction of a mermaid in England. In British folklore, mermaids were unlucky omens, both foretelling disaster and provoking it. Mermaids from the Isle of Man, known as ben-varrey, are considered kinder toward humans than stories from other regions, with various stories of assistance, gifts and rewards.

The mermaid in the Norman Chapel at Durham Castle.

In Eastern Europe, mermaids have a different origin to elsewhere, as all mermaids – or Rusalkas – are restless spirits of the unclean dead. Usually they are the ghosts of young women who died a violent or untimely death, often by murder or suicide, before their wedding and especially by drowning. They can be found at night, dancing together under the moon and calling out to young men by name, luring them to the water and drowning them.

Rusalkas portrayed by Ivan Kramskoi in The Mermaids, 1871. WikiCommons.

Mermaids are also found in other cultures across the world, including China, Africa, and the Caribbean. The common threads usually are that they are beautiful women who either try to lure men to their death, or fall in love with them. Sometimes due to magic, the mermaids are able to walk on land, although there is usually a caveat to this. Whilst there are legends of mermen, the idea that these sea creatures are beautiful women seems to be a far more popular and prevailing legend.

In Medieval Western Europe, the mermaid was often portrayed as an evil, lustful creature, and the fact that they were women only heightened this imagery because contemporary sexism against women meant they were viewed as the weaker sex who tempted men to sin. Part of this reputation probably came from the enduring appeal of the mermaid in folklore whilst the Church was trying to establish Christianity’s dominance in conquered territories and eradicate pagan imagery. Mermaids went against the Christian worldview, and so needed to be vilified. Many medieval depictions of mermaids show them holding a comb and mirror, meant to symbolise the sinful vanity of the mermaids. They became a symbol of lust and temptation, their beauty deceiving young men to go to their deaths. This perhaps explains the frequency of depictions of mermaids in medieval churches – as most of the medieval population was illiterate and couldn’t understand Latin, the language of the Mass, imagery around churches were there to explain doctrine. The pictures and carvings of mermaids were to remind the congregation of the sins of lust and pride.

A mermaid holding a mirror and comb, GKS 1633 Bestiarius England, fifteenth century, and decorative mermaids from Harley MS 4972 f. 20r, 1275-1325.

Under this understanding, then, it is perhaps unusual that the House of Luxembourg, a late medieval royal family, chose a mermaid as their mythical ancestor. In the medieval period, it was not unusual for royals or members of the nobility to claim descent from mythical creatures or legendary men for propaganda purposes – the legend of King Arthur proliferated under Henry II to extend his royal authority. The Luxembourg family claimed that their ancestor, Count Siegfried of the Ardennes, married the female water spirit, Melusine.

Melusine was a popular legend of a water spirit in the medieval period. The story went that Melusine was a form of fairy, spirit, or mermaid, who inhabited forest lakes and streams. One day, a handsome nobleman (his identity changes depending on who is telling the legend) came across Melusine, and persuaded her to marry him. She agreed on the condition that 1 day a week was to be hers alone, and her husband was to never intrude upon her privacy on this day. The man agreed, and they were married and the couple had many children. One day, however, the man lets his intrigue get the better of him and he hides himself in order to watch Melusine bathe. When he sees her in the water, he sees that she has gained the tail of a fish (or sometimes serpent). Melusine flees never to be seen again (in some legends she turns into a dragon before fleeing and curses the magical castle she had created for her and her husband with her disgruntled spirit).

Melusine’s secret discovered, from Le Roman de Mélusine by Jean d’Arras, ca 1450-1500. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The Luxembourgs claimed their link to Melusine from Count Siegfried, who in 963AD bought the feudal rights to the territory on which he founded his capital city of Luxembourg. After this, his name became connected to the local version of the legend of Melusine. In their version of the legend, Melusine magically creates the Castle of Luxembourg on the Bock rock (the historical center point of Luxembourg City) the morning after their wedding. Her legend continues today, with Luxembourg issuing a postage stamp commemorating her in 1997. Jacquetta of Luxembourg, mother of Queen Elizabeth Woodville (who married Edward IV and was mother of the infamous Princes of the Tower), was part of the House of Luxembourg who continued the legend of Melusine in their ancestory. In Philippa Greggory’s works of fiction, The White Queen and The Lady of the Rivers, Jacquetta’s belief of descent from Melusine ties in with the idea that Jacquetta and Elizabeth had magical powers. In reality, we do not know how much Jacquetta seized upon the legend of Melusine; whilst we know that she had a copy of a medieval romance entitled Mélusine, the romance was a popular one at the time, and copies were found among the inventories of other high-born ladies.

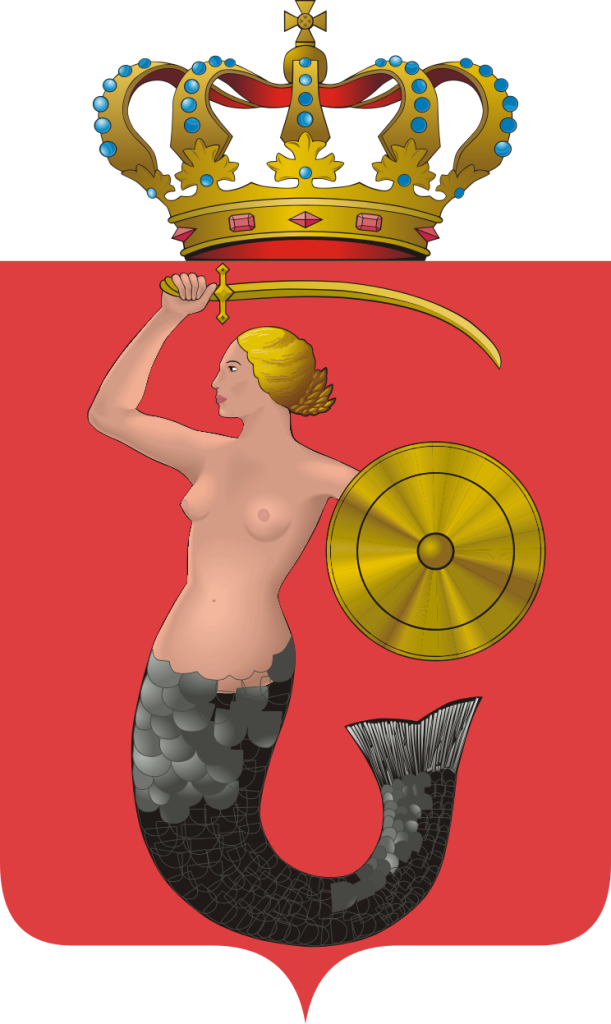

The legend of Melusine was not just one the Luxembourg family seized upon, and many other families and regions of northern Europe used the story and included mermaids in their heraldry. French heraldic tradition includes double tailed mermaids and mermen being used on the shield to symbolise eloquence – again, surprising considering the association of mermaids with negative qualities. A shield and sword-wielding mermaid (Syrenka) is on the official coat of arms of Warsaw and images of a mermaid have appeared on its arms since the middle of the 14th century.

Melusine carrying the arms of Luxemburg/Bohemia and Lusignan/Cyprus. From Estienne de Lusignan: La Généalogie des 67 très illustres maisons, partie de France, partie étrang`res, issues de Mérovée. Paris, 1586.

Reported sightings of mermaids continue to the modern day, and the medieval period was no different. Whilst sailing off the coast of Hispaniola in 1493, Columbus reported seeing three “female forms” which “rose high out of the sea, but were not as beautiful as they are represented”. There was also an apparent merman found in Suffolk a few centuries earlier. According to the chronicler Ralph of Coggeshall, a naked wild man, covered in hair, was caught in the nets of local fishermen around 1167. The man was brought back to Orford Castle where he was held for six months, being questioned or tortured. The man never spoke and would only eat fish, and behaved in a feral manner throughout his capitivity. The wild man finally escaped from the castle and was presumed to have returned to the ocean. Later accounts described the captive as a merman, and the incident appears to have encouraged the growth in “wild men” carvings on local baptismal fonts – around twenty such fonts from the later medieval period exist in coastal areas of Suffolk and Norfolk, near Orford.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

John William Waterhouse, A Mermaid, 1901. WikiCommons.

Many theories abound for the legends of mermaids. Many believe that sightings such as Columbus’ were probably of manatees or dugongs. As legends of mermaids are prevalent in areas with a strong coastal tradition, such as the United Kingdom or northern Europe, it is natural that those who were often out at sea and relied on good weather for their lives would create superstitions related to their work. Rather than blame God for a storm that sunk a boat, or a ship mysteriously wrecking on rocks, it is easier to blame a malicious creature who wants to kill human men. In a medieval culture where the beauty of a woman could often hold her under suspicion of being of ill-intent and evil character, luring men to lustful acts, it is easy to see how mermaids were usually associated with beauty and vanity. Popular interest in mermaids continues today, and there are over 130 public art mermaid statues across the world, not to mention their popularity in film and television. It seems that even 3,000 years after their first appearance in legend, we cannot resist the allure of a mermaid.

Previous Blog Post: Stand and Deliver, Your Money or Your Life: Female Highwaymen of the Seventeenth Century

Previous in Mythical Creatures: Medieval Vampires

You may like: Fairy Tales or Medieval Reality? Historical origins of fantasy stories

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Reblogged this on VIRTUAL BORSCHT .

LikeLike

This is so fascinating, especially with mermaid everything so popular at the moment. Impeccably researched by the way

LikeLike

Thank you! Yes they are, I also find it interesting how ideas about mermaids haven’t really changed much at all over time, whereas other legends you do see an evolution (eg the “good vegetarian vampires” you see today)

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The TRUTH is the LIGHT.

LikeLike