When people think of the medieval or early modern period, often it conjures images of the witch trials across the western world. These people are considered a superstitious bunch, deeply religious, and very suspicious of magic. Whilst there is of course substance to some of these ideas (and I have already discussed one case of an alleged royal witch), medieval people at royal courts did enjoy the suspended disbelief of magicians in the same way that we do today. Part of the reason magic at court was a dangerous thing to practice was that there was a fine line between acceptable and unacceptable magic, magic that bordered on science, and magic there to entertain.

Medieval people were not living in constant crippling fear of magic, and magic often featured heavily in chivalric romances – the booming popularity of Arthurian romances that continues even today demonstrates this. As such, the blurring of ‘magic’ and science often featured at European courts as something to entertain crowds. Whilst we think of machines as more modern inventions, there were some astonishing ‘machines’ created to astonish the court that grew out from performance magic.

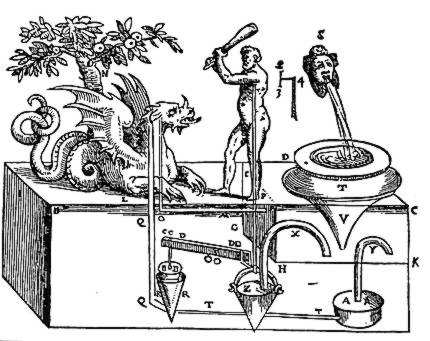

Automatons originated in Ancient Greece where they were used for many things from toys to religious ceremonies to science. Rhodes was apparently a centre for mechanical engineering, with one poet remarking “The animated figures stand/ Adorning every public street/ And seem to breathe in stone, or/ move their marble feet.” It was from this culture that the idea of creating machines (often to look like animals or even people) that seemed to move all by themselves continued through to the medieval period.

In Emperor Theophilos’ palace at Constantinople in 949, an ambassador describes the automatons decorating the place:

“lions, made either of bronze or wood covered with gold, which struck the ground with their tails and roared with open mouth and quivering tongue,” “a tree of gilded bronze, its branches filled with birds, likewise made of bronze gilded over, and these emitted cries appropriate to their species” and “the emperor’s throne” itself, which “was made in such a cunning manner that at one moment it was down on the ground, while at another it rose higher and was to be seen up in the air.” (quotes via Wikipedia)

Leonardo Da Vinci, famous for many things, wrote extensively about automatons, and his personal notebooks are littered with ideas for mechanical creations. One of his designs included an armoured German Knight which was to be powered by an external mechanical crank and used cables and pulleys to sit, stand, turn its head, cross its arms and even lift up its metal visor. Evidence suggests that Da Vinci may have actually built a prototype in 1495 while working under the patronage of the Duke of Milan, and in 2002 a NASA roboticist attempted to create a version of Da Vinci’s knight; it proved fully functional, showing the genius of his invention.

The following century, another ‘robotic’ man was created, this time for Philip II of Spain. The story goes that Phillip II’s son and heir suffered a head injury, and Philip vowed to God that he would deliver a miracle if his son was spared. When the Prince recovered, Phillip II commissioned a clockmaker and inventor named Juanelo Turriano to build a lifelike recreation of beloved Franciscan friar Saint Diego. Completed sometime in the 1560s, the monk was 15 inches tall and was powered by a wound spring. Three small wheels were concealed beneath the monk’s robe and iron levers move the wheels. Artificial feet stepped up and down to imitate walking, and the friar’s eyes, lips and head all moved in lifelike gestures. The monk could walk in a square pattern mouthing prayers, nodding its head, beat its chest with its right arm and kiss a rosary and cross with its left. The 450-year-old device is amazingly still operational today, and is held at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

The Franciscan monk. If you want to see footage of the monk in full automaton action, there is a video on Youtube here (though I take no responsibility for any nightmares incurred as a result of watching it)

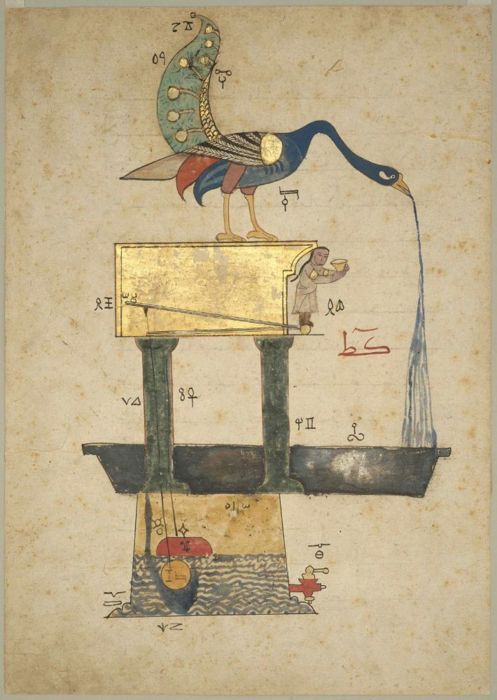

Some automatons had more of a practical purpose (though with entertainment still at the heart). In the early 13th century, Ismail al-Jazari, an Islamic polymath, wrote The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices where he described 100 mechanical devices. One such device was the “peacock fountain” which was a complex hand washing device. Pulling a plug on the peacock’s tail released water out of the beak, and as the dirty water from the basin filled the hollow base a float rose and activated a switch which made a servant figure appear from behind a door under the peacock and offer soap. When more water was used, a second float at a higher level tripped and caused the appearance of a second servant figure with a towel. It sounds pretty impressive! When you think of the automatic taps and hand-driers we have in public bathrooms today, Al-Jazari’s invention sounds just as impressive, if not more so!

These automatons were not always solely for courtly entertainment, however. The day before his official coronation in Westminster Abbey in 1377, Richard II of England was ‘crowned’ by a golden mechanical angel – made by the goldsmiths’ guild – during his coronation pageant in Cheapside. This was not only a show of devotion and loyalty from the goldsmiths, but it would have wowed the crowds, particularly those who weren’t part of the court who probably hadn’t seen such a creation before. It certainly would have emphasised the mysticism behind the crown, and the religious connection between the King and Heaven.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

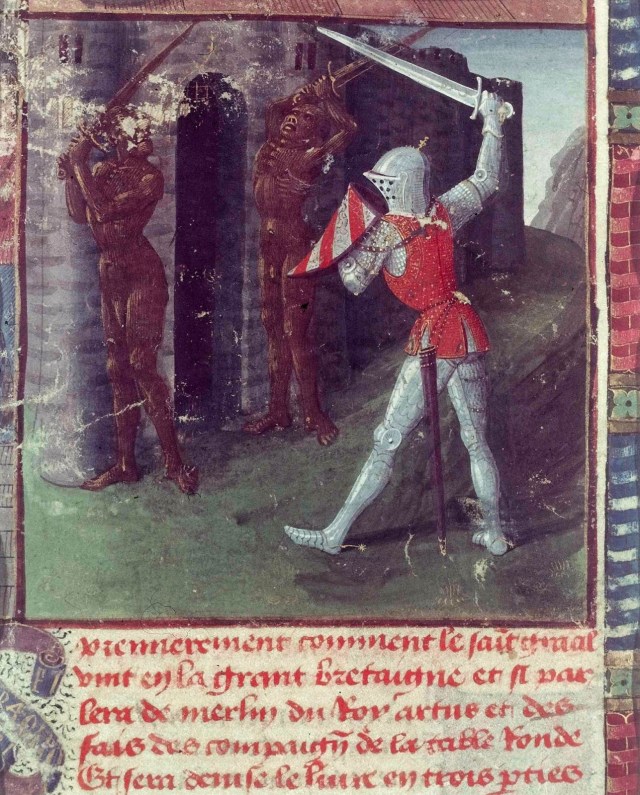

Automatons featured heavily in Chivalric romances, where the blurred line with magic is evoked. Whilst ordinary people knew that automatons were machines created by men, even if they didn’t know how they worked, it is easy to see how it inspired thoughts of magical creations. Often in medieval romances there were mechanical creatures brought to life by magic, clearly inspired by automatons seen at court. In a thirteenth century version of Lancelot of the Lake, Lancelot fights two copper knights at an enchanted castle. Many romances also included appearances of metal-like birds singing in trees, brought to life by magic, again drawing inspiration from scenes such as that at Emperor Theophilos’ palace.

So whilst we may think of robots and machines as a very recent thing in human history, in fact they have been around for a lot longer. The most spectacular creations were in the East, where science and mathematics were more advanced, and the best automatons in Western courts were usually gifts from Eastern rulers. It is certainly easy to see how they evoked ideas of magic and found their way into the popular imagination through magical chivalric romances.

Previous Blog Post: The Biggest Party Ever? The Field of the Cloth of Gold

Previous in Miscellaneous: How Medieval Medicine is Helping us Today

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Further Reading: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Automaton

http://www.medievalrobots.org/2011/04/cleopatras-automata.html

https://aeon.co/essays/medieval-technology-indistinguishable-from-magic

Very interesting and I couldn’t resit a look at the automated monk video.. a bit scary indeed!

LikeLike

Thank you! Yes there is definitely something unsettling about it!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Lenora's Culture Center and Foray into History and commented:

Love history. I can never get enough and I love learning new bits of history. Great post

LikeLike

I wrote a book on this topic, called Medieval Robots, which features several of the (previously unpublished) images here, as well as much of the information contained in your post. Are you familiar with my book? It seems you might be. The book took me 10 years to research and write. Several others have written about the robotic monk and Hesdin; perhaps you’re also familiar with the work of Elizabeth King or Scott Lightsey. I bring this up because it would be perhaps interesting to your readers to know where they could learn more about these objects, and it would be respectful to the people who’ve spent years of their life, their own money, and a lot of hard graft to do this work, not to mention the talented, underpaid staff of university presses, like the people who made my book a material reality.

LikeLike

I’m afraid I haven’t heard of your book – I’m sorry if you feel I may have stolen material from it. I got most of my information and images from wikipedia, as well as some general information I gathered from various modules at University and I think I may have used a BBC History article at one point as well

LikeLike

Thanks for your response. I’d be grateful if you could direct me to the Wikipedia articles you used; I’ve been unable to find the material mentioned in your blog post in Wikipedia articles on robots/automata.

LikeLike

Of course: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Automaton#cite_ref-Safran1998_15-0 this is the main reference page I used. There I got the information about Emperor Theophilos and Al-Jazari under the “medieval” section. Under Renaissance, it mentioned Leonardo Da Vinci’s robot, and a quick google search led me to an article about the modern recreation. The Renaissance section also mentioned the mechanical monk which reminded me that I thought I had heard of that through the British programme QI (it may have been from elsewhere that’s just where I thought my memory may have been from), and again a quick google led me to a few news articles about it and the discovery of the Youtube video showing it in action.

http://www.medievalrobots.org/2011/04/cleopatras-automata.html this page gave me the information about the Hero of Alexandria

https://aeon.co/essays/medieval-technology-indistinguishable-from-magic I believe this may have been the page where I found Richard’s crowning

http://ir.uiowa.edu/mff/vol46/iss1/7/ This article is where I got confirmation of the information about the chateau at Artois mentioned in the medieval section of the above wikipedia link (I see now you authored the last two links)

Finally i found the Lancelot image and story via a google image search for medieval automata, and the information about the metal like birds etc was just general information I remembered from something I read at University

I hope that helps. If you look at my other articles you’ll see that usually when I rely substantially on a piece of work, I do tend to reference them – I just didn’t put any here as as I said, the majority of my information was found via wikipedia or museum websites

LikeLike