On this day, 5th September, 1666, the disaster that was the Great Fire of London finally drew to a close. It had burned for 3 days and completely destroyed the medieval part of the city within the old Roman walls. By the time the fire died out, 13,200 houses, 87 parish churches, most of the City authority buildings and St Paul’s Cathedral had all been decimated. Amazingly, however, it is believed that as few as 6 people may have died.

The people of London had not been having a good time. In 1660, the monarchy had been restored to general popular acclaim, and partying, fun, and luxury had returned to the country – a great thing for Londoners. However, 5 years later in 1665 the Great Plague once again struck the capital to devastating effect. The Bills of Mortality for that year show over 68,500 deaths from plague in London, although contemporaries estimated it was as much as double that due to difficulties in keeping records during such an outbreak. Contemporaries estimated around 200,000 people died in total from the Great Plague – today it is estimated that almost a quarter of London’s population may have died across 18 months.

Charles II, who had been restored to the throne in 1660, and was King across the Great Plague and the Great Fire of London.

By February 1666, London was judged safe enough for the King and wealthy people who had been able to evacuate the city to return. Trade restarted, and people flocked to the city believing they could make money because of the drop in population opening up labour. By the end of March, Lord Clarendon, the Lord Chancellor, said that “the streets were as full, the Exchange as much crowded, the people in all places as numerous as they had ever been seen”. Parliament passed the Rebuilding of London Act to try and improve the city to prevent another such outbreak occurring and the results of the act did eventually lead to a healthier living environment in the city.

It is in this context, then, that we come to the second devastating event to hit the city in less than 2 years. Amazingly, we know exactly where the fire started. It famously started in a bakery on Pudding Lane owned by Thomas Farriner shortly after midnight on Sunday, 2nd September. The fire started innocuously enough; the family were trapped upstairs but managed to climb out of their window to the house next door, although their maidservant was too scared to attempt this, and she became the first fatality. The neighbours were left to try and extinguish the fire themselves, but after an hour with the fire still burning, parish constables arrived to help. They decided that the adjoining houses needed to be demolished to prevent the fire from spreading (at great protest, understandably, from the inhabitants). The Lord Mayor arrived to sort out the situation, as he had the authority to override the inhabitants.

A concept sketch of what Pudding Lane may have looked like at the time. From Journal of Digital Humanities.

At this time, most of London was still built out of wooden buildings that were all squashed tightly together, often with several floors (usually up to 6 or 7 floors) that overhung the streets and other buildings. Streets were narrow and winding, and houses were so close to each other – particularly the upper floors that projected into the street – that it was often said people living on opposite sides of the street could shake hands through their upper floor windows. Obviously, this made for a dangerous fire hazard, and this had been proven by several major fires in the past. Part of the Rebuilding of London Act recently passed was to widen streets, ban wooden buildings and overhanging gables, and ensure that future buildings were built in stone or brick. This act had not had time to fix the streets before the fire, however.

As a result, by the time the Lord Mayor reached Pudding Street, the fire had already spread to the adjoining houses and was moving in the direction of flammable stores by the river front. Experienced firemen were on the scene, who told the Mayor that houses needed to be demolished to stop the fire in its tracks, but as most of these buildings were rented and the owners could not be found, the Mayor did not want to demolish them. He is remembered as having apparently exclaimed the words “Pish! A woman could piss it out” before leaving the scene of the fire.

By Sunday morning, the famous diarist Samuel Pepys, who was a senior in the Navy Office, surveyed the fire from the turrets of the Tower of London. He wrote that by this time, the winds had caused the fire to become a conflagration which had reached the river front. It had reached London Bridge, which at this time still had houses and buildings on it, all of which were now burning. Pepys estimated that by this time around 300 houses had burned down. People were fleeing to the river front and getting into boats to escape, bringing their goods and furniture with them where possible, sometimes simply throwing them straight into the river itself.

People fleeing Newgate with whatever goods they could carry. Museum of London.

As morning turned into afternoon, a high wind was hitting the city and was fanning the flames. By now, people had given up the impossible task of trying to extinguish it, and a mass evacuation was underway. This, however, only made the job of firemen even more impossible, as the narrow lanes were too clogged with people to pass through. The mayor had reappeared, and upon receiving Pepys’ orders from the King to pull down houses, responded that he was already trying to do so, but that the fire was approaching quicker than they could get the houses down. The fire had become so large that it was beginning to create its own weather; the narrow streets and small distances between buildings were creating the chimney effect, leaving a vacuum at ground level which supplied fresh oxygen to the fire. The uprush of different temperature air, aided by the winds already in the city, meant the fire was now spreading north and south, as well as the original easterly direction.

As evening fell on the Sunday, Pepys and his family surveyed the fire from the other side of the river. He wrote that the fire was “only one entire arch of fire from this to the other side of the bridge, and in a bow up the hill for an arch of above a mile long: it made me weep to see it”. The fire showed no signs of slowing across the night, and by Monday morning the self-feeding fire was continuing to spread far north and south. The river to the south largely stopped the spread of the fire, but as it had burnt the houses on London Bridge, there were fears that the fire would spread south across the bridge into Southwark. Luckily, though, there were firebreaks on the bridge and a long gap between the buildings which stopped the fire passing through.

The north of the city was not so lucky, however. It reached the financial district of the city and the houses of bankers started to burn down by the afternoon. There was a huge rush to save the piles of gold coins stockpiled there before they were melted by the fire – the loss of these huge reserves would have crippled the entire country. The wealthy districts and government buildings were now being caught in the fire, but as the fire had now been raging for nearly 2 days with no signs of slowing down, many people seemed to have been overwhelmed with despair and there was very little effort to save these districts.

The city burning, with the Thames full of ships rescuing people. Unknown artist.

The scene in late afternoon on the Monday was described by John Evelyn, another diarist, thusly: “the whole City in dreadful flames near the water-side; all the houses from the Bridge, all Thames-street, and upwards towards Cheapside, down to the Three Cranes, were now consumed”. In the evening, the river was packed full of boats trying to ferry people and goods away from the fire, and the gates that guarded all the entrances to the city were jammed with people and carts trying to escape to the open fields outside the city. Miles of these fields were full of people and goods taking refuge.

As was inevitable in such an inexplicable fire, people began to look for blame. The fire was so immense it couldn’t have been caused by one bakery, and because winds were carrying sparks across great distances, setting fires to houses not immediately in the path of the fire, people began to suspect that new fires were being set on purpose. This led to fears that foreigners were about to invade, and they were setting fires to cause panic and disorganisation, and to distract soldiers and the government. Homes and shops owned by foreigners began to be attacked by mobs. This fear was made even worse when the London Gazette and the General Letter Office burned down; these were the main points of communication for the nation, and with these no longer able to offer more reliable information, rumours proliferated.

Towards the end of the day, that now-reviled London Mayor had apparently fled the city. In response, King Charles took control, overriding the City authorities (who technically should have been in control) and assigning his brother James, Duke of York, as head of operations. James and Charles finally proved to be somewhat effective in tackling the fire. James sent men to key spots along the perimetre of the fire with authority to demolish any building deemed necessary to stop the spread of the fire. James and some of his men patrolled the streets all day to try and keep order, including rescuing any foreigners from angry mobs. This gave huge popularity to the Crown; one person, writing a few days after the event, said that “The Duke of York hath won the hearts of the people with his continual and indefatigable pains day and night in helping to quench the Fire”. King Charles himself was said to be working manually to try and help quench the flames, throwing water on the fire and creating firebreaks. Meanwhile, the old mayor was one of the most hated men in the country.

James, Duke of York, the future James II.

Unfortunately, all of these efforts were still no match for the huge conflagration. The next day, Tuesday, was the day that caused the greatest destruction to the city. The fire managed to jump across the river at Fleet Bridge, outflanking some of James’ firemen, causing them to flee for their lives. In more positive news, some of his other firefighters in the north had created a sufficient firebreak to contain the fire for most of the afternoon, until it finally managed to cross into Cheapside.

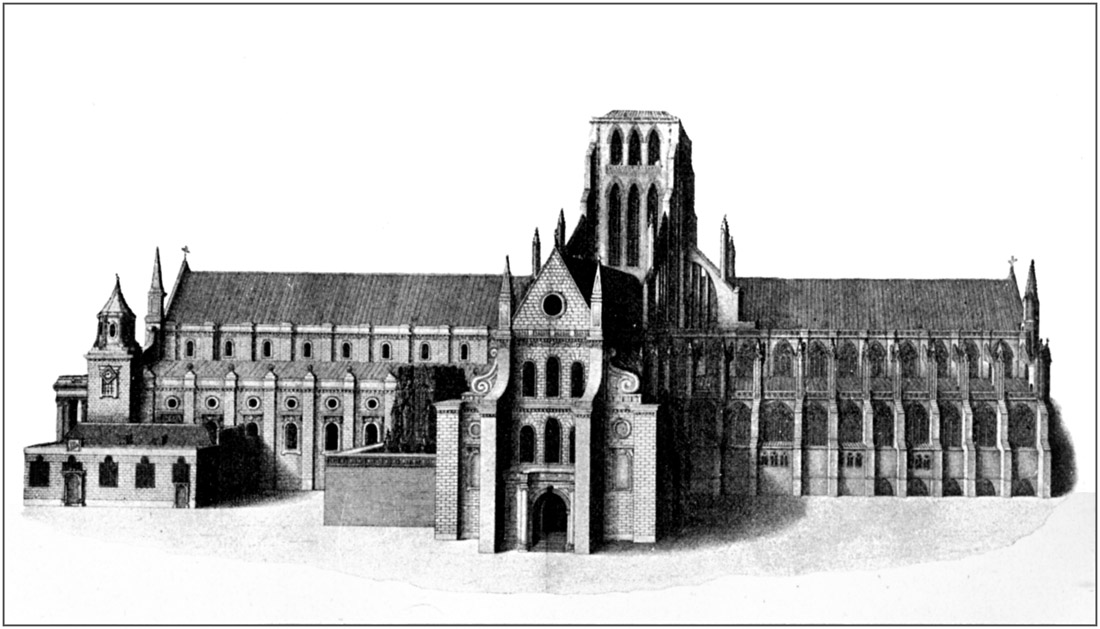

On Tuesday evening, St Paul’s Cathedral finally caught fire. It had been used as a refuge, packed to the brim with goods, printers, and books, in an attempt to save important chattels of the city, as it was believed the thick stone walls and natural firebreak surrounding it would protect it. However, it was covered in wooden scaffolding ready for restoration work, and this scaffolding now caught fire, eventually decimating the historic, holy building. The fire now took on an even more dangerous turn; it was moving towards the Tower of London which held a huge arsenal including enormous quantities of gunpowder. Needless to say, this would be devastating if it caught fire. Those in charge of the Tower, however, managed to create a sufficient firebreak to stop the fire reaching them.

St Paul’s Cathedral as it looked in 1658 before it burnt down in the fire.

In the late hours of Tuesday night, that dreadful wind finally ended, and the various firebreaks across the city began to hold against the incessant flames. By Wednesday, 5th September, more than 3 days after the fire started, the flames finally began to subside. Pepys surveyed the city from the steeple of Barking Church, remarking that the decimated city was “the saddest sight of desolation that I ever saw”.

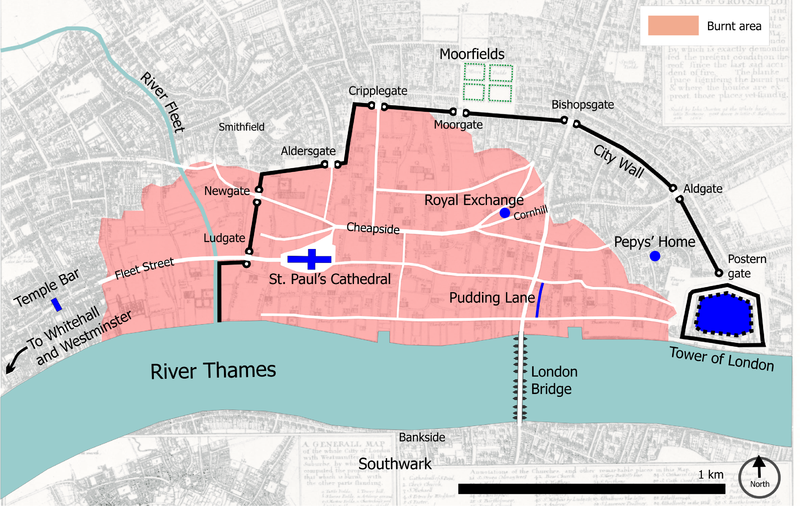

The city certainly was desolate. Tens of thousands had lost their homes, important buildings had been destroyed, and objects of huge importance to the running of the city along with it. Evidence of melted steel in the wharves, and from melted pottery from Pudding Lane, shows that the fire reached at least 1250 °C. As well as all the destruction mentioned at the start of the post, 44 Company Halls (centres of trade), the Royal Exchange, the Custom House, Bridewell Palace, numerous prisons, and 3 city gates were all destroyed. The cost of damages is estimated at around £10,000,000 in the currency of the time – well over £1 billion today. It truly was devastating.

The total area that the fire affected. WikiCommons.

Some accounts state that as few as 6 people died, but most were unanimous that death tolls were in the single figures. Many historians today dispute that the death toll could have been this low, saying that smoke inhalation must have killed many, not to mention the sick, old, very young, or otherwise infirm who surely would have been unable to escape such a raging fire. If the fires got to that high a temperature that it melted steel, it would probably have also melted bones of those who died, and even small fragments that survived would have largely gone unnoticed in amongst the extensive rubble. This again would mean that many who died would have gone unrecorded – particularly if they were poor and unknown to begin with. Even if so few died in the actual fire, there is also the point that many died in the aftermath – with food so scarce, and so many people homeless and destitute, many died from hunger or exposure during the winter that followed.

King Charles did much to try and reduce the damaging effects of the aftermath of the fire. He encouraged the homeless to move away from London, where there were few resources and so much damage (also conveniently reducing the risk of a rebellion against the monarchy), and ordered all towns and cities who may receive refugees from the fire to allow them to settle there and continue whatever trade they were trained in. He also established a Fire Court to settle disputes between tenants and landlords to decide who should pay for the rebuild, based on who had the ability to pay. The court ran for just over 5 years, and cases were heard swiftly, usually being resolved within a day. This was a huge help to the city, as it greatly sped up the urgent rebuilding which would have otherwise have been delayed in lengthy legal battles.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

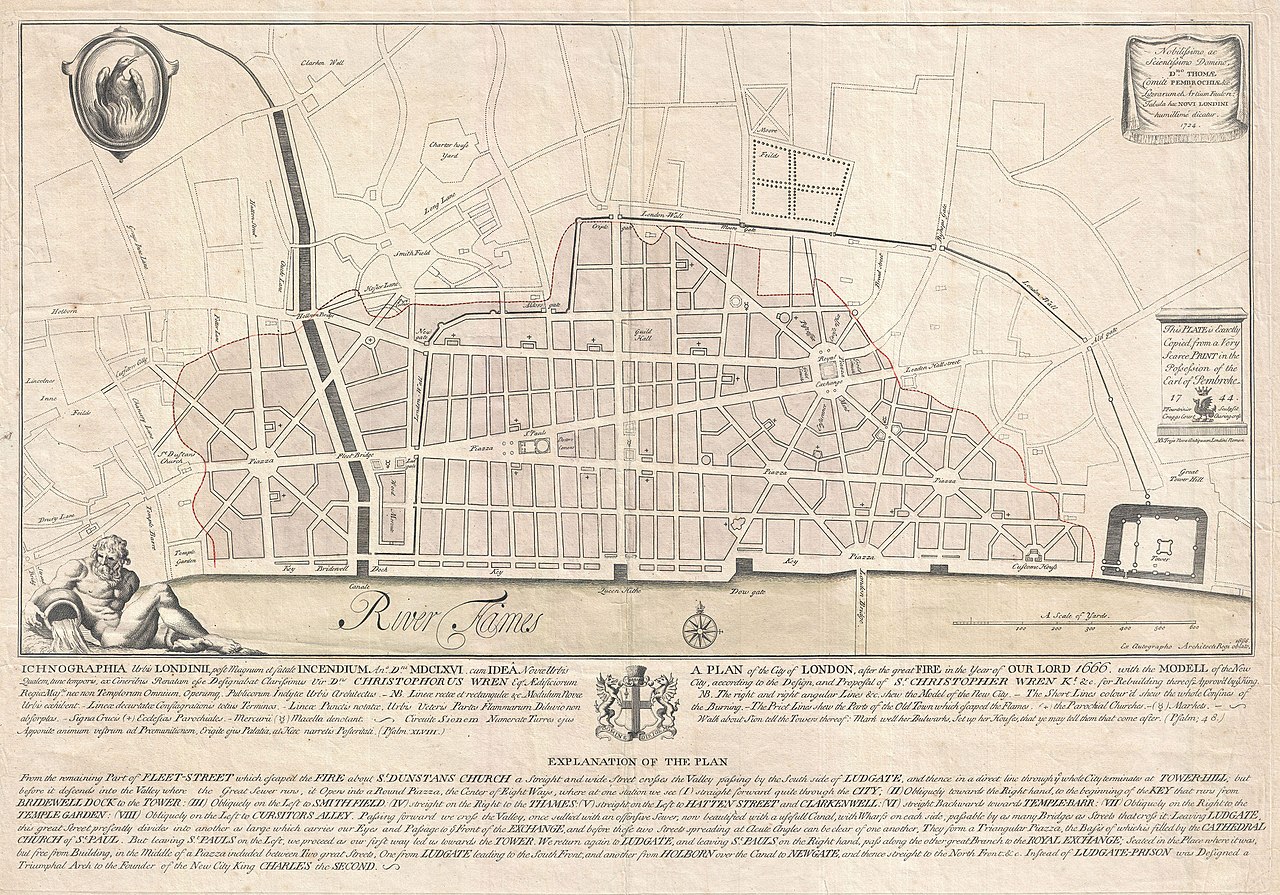

Charles also encouraged rebuilding planning schemes which would have rebuilt a grand, Baroque city. However, these plans all fell through because of a shortage of labour, and no way to plan compensation to current owners of plots and properties. The rebuilding did, however, enable the implementation of the Rebuilding of London Act, meaning that whilst most of the old street plan was recreated in the rebuilding, wider streets and open, accessible wharves, with no housing obstructing access to the river, and all built out of stone or brick, meant that both hygiene and fire safety improved.

Christopher Wren’s suggested plan to rebuild the City of London. WikiCommons.

London had certainly been decimated over the past two years, and it would take a long time to repair all of the damage caused. The upcoming winter would cause great suffering and death to many as a consequence of the fire. Only about 1/5th of the city was left standing, and the rebuilding took over 30 years. Around 100,000 people were probably made homeless. However, the city did manage to slowly recover, and the recently-restored monarchy gained a lot of popularity from the people for its handling of the situation. London climbed its way back up.

Previous Blog Post: Legendary People: Lady Godiva

Previous in Important Events: The Spanish Armada of 1588

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

The blog has been quiet for quite a while, as it’s been a very busy month for me. But I am back and ready to produce more content for you all! If there are any topics, events, people, etc you would like to see me cover, please leave a note in the comments!

Read more about the Great Fire of London here:

http://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/The-Great-Fire-of-London/

http://www.historyextra.com/article/united-kingdom/10-facts-great-fire-london

Excellent post. And isn’t King Charles lovely?

LikeLike

Thank you! And yes I think he comes out very well from this – seemed to genuinely care about the wellbeing of the citizens and really wanted to help!

LikeLike

I must say I really enjoyed this entry on a topic which very much interests me. I still find it hard to believe that only 6 people lost their lives. Your entry provides a great academic accompaniment to my own entry on the Monument which, of course, commemorates the Great Fire and the subsequent rebuilding of the city. I hope you don’t mind me adding a link from my entry to yours.

https://ramblingwombat.wordpress.com/2017/03/04/the-monument-to-the-great-fire-the-monument/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Yes, it’s certainly one of my favourite events (if that doesn’t sound too odd considering the devastation!). I think it’s so interesting seeing how they tried to tackle it, and how everybody came together, and how it is likely not many people died as you would expect from such a huge disaster. And not at all! I look forwards to reading about it.

LikeLike