Today we are very lucky to have a guest author! Simon Forder, a writer, researcher and historian who specialises in castles, has written a great introductory post about their origins in Britain. Starting in the Norman period, he explores what different types of castles appeared in Britain after the conquest, and just how original they may have been. You can find him on Twitter, Facebook, or via his website. Over to you, Simon!

Motte at Twmbarlwm, South Wales; late 11th/early 12th century. Picture taken by Simon.

Castles appear in many guises to us. Once massively dominant structures in the medieval landscape, they are inspirational reminders of our past, enabling the visitor to wonder and imagine the splendours of a bygone age. However, in most cases today they are sad remnants of their former glory, often little more than humps and bumps in the landscape.

Britain has a long history of castles, traditionally beginning with the arrival of the Normans under William the Conqueror in 1066 on the south coast of England. Those with a more detailed knowledge of the period will know that some Normans were already in England a few years earlier, in the reign of Edward the Confessor, and that some castles were founded by them in the Welsh Marches before Duke William invaded. Fewer people will know that there is now scholarly debate over these early castles, and that the Norman builders had in fact used existing defensive works and modified them.

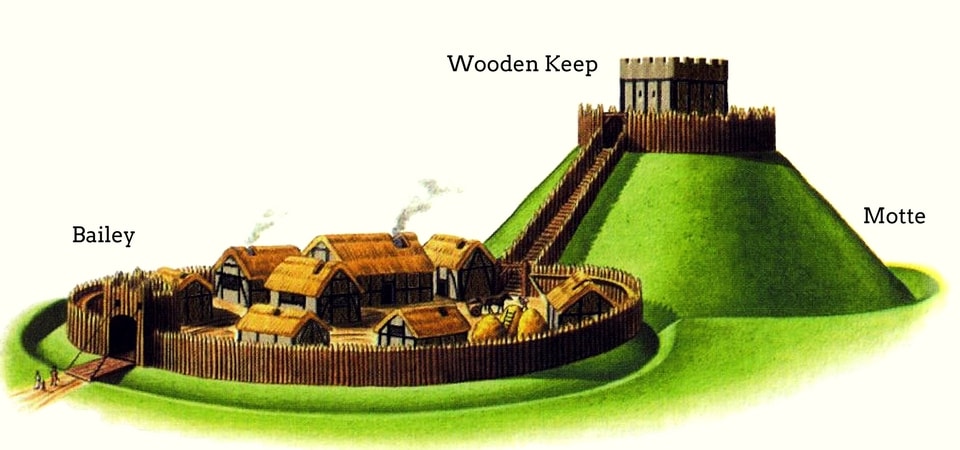

The “classic” Norman castle is the motte and bailey, consisting of a tall conical mound (the motte) with a tower on the top, and a kidney-shaped enclosure adjacent (the bailey), all surrounded by a ditch. The bailey was usually enclosed by a bank, thrown up from the ditch and topped by a wooden palisade. Although contemporary accounts talk of castles being erected in days, and this has led to a common belief that a motte and bailey castle was quick and easy to build, even a modest castle of this nature would take several weeks to excavate, with larger ones taking several months.

The classic layout of a Norman Motte and Bailey castle. Via CastlesWorld.

The notion that we have, therefore, of these castles springing up like a rash across England and Wales as the Normans took over the country is mistaken. In a time of conquest, with a limited number of armed men at their disposal, the Normans could not do this. How, then, did they manage to subdue the population so quickly? The answer lies partly in considering some of the very earliest sites we know they used in southern England, and later in Wales, where the military activity is perhaps more easy to follow. It also lies in reassessing the information that we have about the conquest itself.

Whilst preparing for his invasion, Duke William had ordered the construction of three pre-fabricated castle kits. This meant that as soon as he was able to identify a suitable location, the cut and drilled timber could very quickly be assembled on site. One of the Norman chronicles describes how the first of these was erected before evening on the day of landing, and used to keep all the army stores inside. It is believed that this castle was erected within the ruined stone walls of the Roman fort at Pevensey. The following day, the Normans marched along the coast to Hastings, where the other two prefab castles were erected. It is to be assumed that one of these was erected on the hilltop where the stone castle was later built. The location of the other is unknown, but there has been much coastal erosion here, so the site may have been lost.

The Bayeux Tapestry, embroidered in the 11th century, shows several castles. Here, workmen build the castle at Hastings during William’s invasion.

The earliest castles of the Normans were therefore far more transient structures than the motte and bailey castles, and it should come as no surprise to understand that they utilised existing defensive structures wherever possible at this early stage of conquest. Indeed, despite the heavy losses of the English army at Fulford Gate, Stamford Bridge, and Hastings, the English still chose to elect the 15 year old Edgar Aetheling as their king. It was still to take several years before England submitted fully.

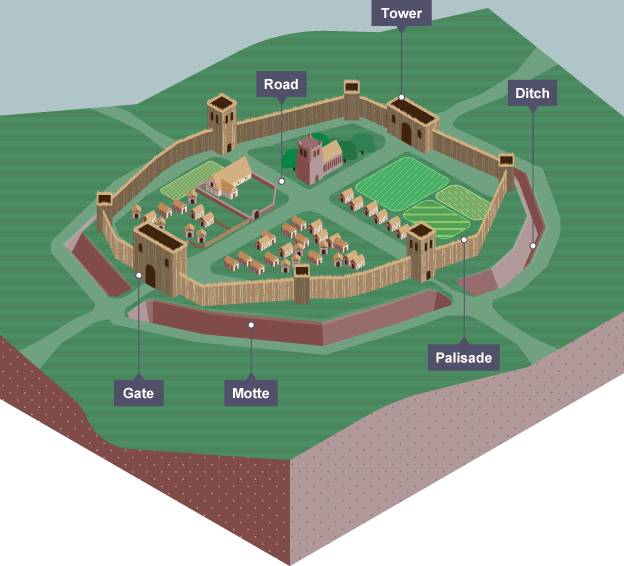

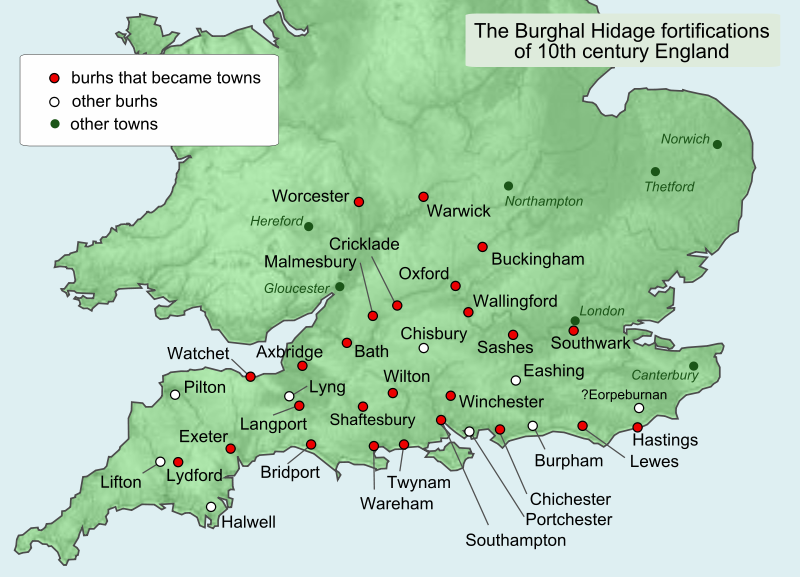

So, what was here before the Normans came, and can these structures truthfully be described as castles? During the 9th and 10th centuries, a series of burhs were created to act as centres of defence against the predations of the Vikings. These were in Wessex and Mercia, and the defences were massive earth ditches and banks, the banks revetted in timber with a palisade above, the timber later replaced with stone. These were military centres, with additional functions as markets and often had mints associated with them. Some were new foundations, such as Oxford and Wallingford (the defences of Wallingford can still be seen today), others were recommissioned Roman sites like Winchester and Portchester, and others utilised Iron Age defences, like Dover.

In addition to these royal defensive works, there were an unknown number of private defensive sites built by the English nobility. These were provided with an impressive defensive ditch and bank, usually topped with a timber palisade, and a “burh-geat” which was the entry gate. It is now believed that in order to emphasise status, some of the lesser nobles erected larger and more impressive gate-towers if their site was perhaps less than overwhelming. A well-known statement by Archbishop Wulfstan of York says that someone might achieve the status of a thegn if he had five hides of his own land, a bell and a burh-geat, and a seat and special office in the kings hall. We have to therefore assume that EVERY thegn in England had a residence with a burh-geat – and that means a lot of defended residences.

A diagram of an Anglo-Saxon Burh, via BBC.

Many Anglo-Saxon burhs eventually developed into significant towns. This diagram shows burhs that are known to have existed in the 10th century in Southern England, showing how many went on to become towns that still thrive today. WikiCommons.

A very useful example is set by a site in Lincolnshire called Goltho. Here, in about 850AD, a defensive bank and ditch were erected around a group of domestic buildings including a hall. This was later rebuilt within the exiting defences, and then rebuilt a second time, this time with the defences enlarged and strengthened. Sometime between 1080 and 1150, a small motte was then erected within the enclosure, before being levelled and rebuilt to a new design. The “Norman” motte and bailey castle was in fact of English origin, with only the motte and its timber summit tower dating to the Norman period.

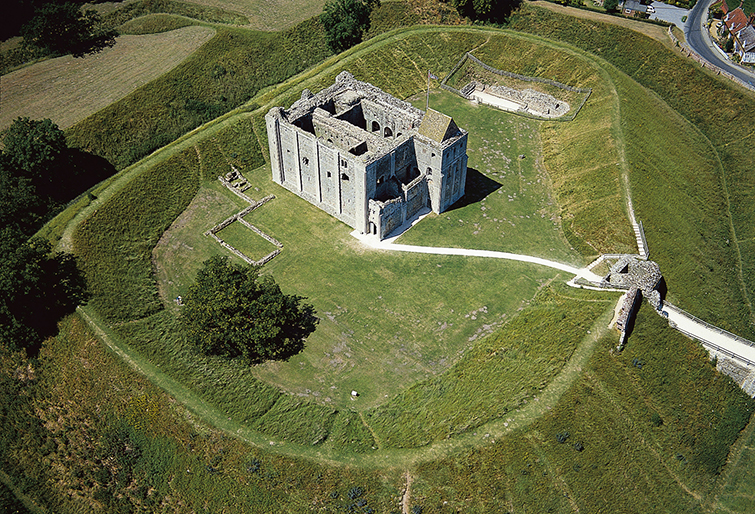

In fact, there are a large number of castles occupied in the Norman period which do not have mottes, but consist of an impressive ditch and bank surrounding an enclosed area. These structures are known as ringworks, a particularly impressive example being at Castle Rising in Norfolk. Increasingly it is becoming recognised that some of these sites were occupied during the pre-conquest period, although it is still seems to be controversial to refer to them as castles.

Bailey of Castle Acre, Norfolk, c 1080, strengthened c 1140. Picture taken by Simon.

Castle Rising, Norfolk. Via English Heritage.

It seems to me particularly inflexible to insist that the castle was a structure which was founded by the Normans, when structures which are indistinguishable from them in both design and function were clearly present in England prior to their arrival. Next time, I will turn to Scotland, before coming back to look at the castles of these pesky Normans.

Great thanks to Simon for writing for us, and we look forwards to reading the next post in his series! Part two can be found here.

Previous Blog Post: When Pineapples Were The Height Of Luxury

You may like: What happened after 1066? The Harrying of the North

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

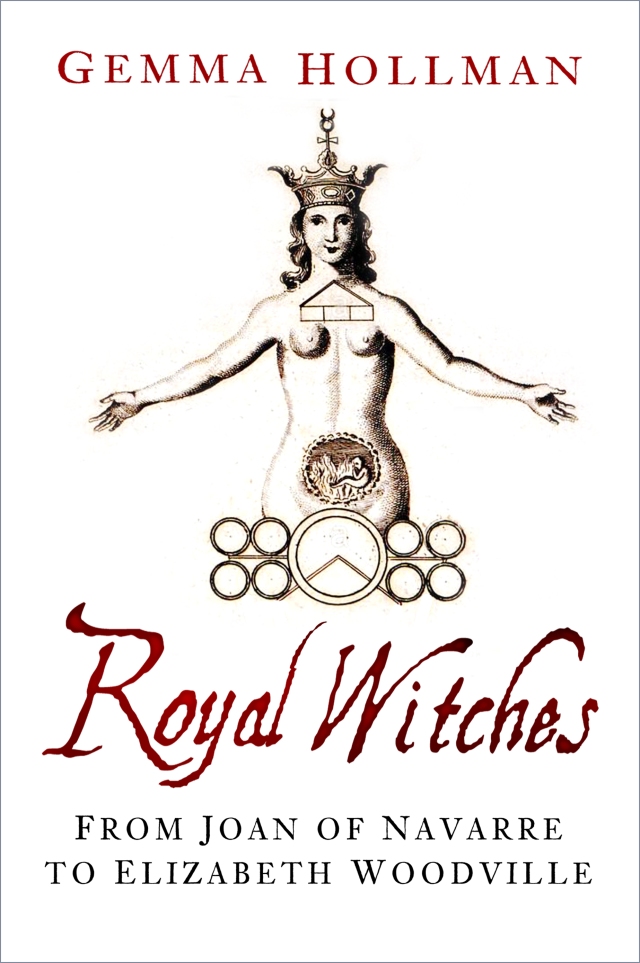

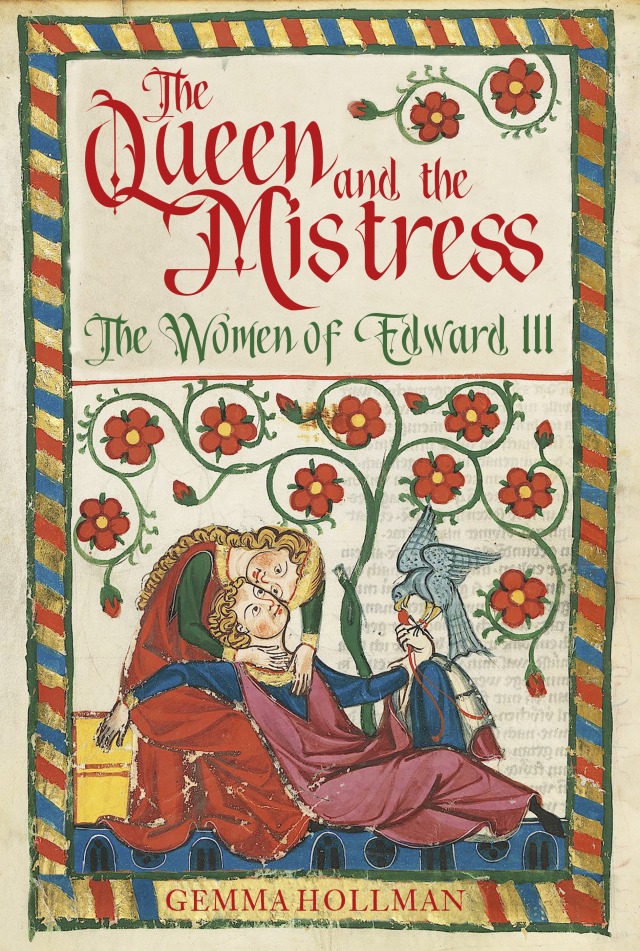

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

I love the idea of pre-fab castles.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know, sounds fantastic! And so ingenious for the time!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh I love this! Fascinating. I recognise Clifford Tower, (the header photo), in York. Stunning and amazing history

LikeLiked by 2 people

Glad you enjoyed! Yes, I took the picture of Clifford’s Tower, such a striking sight in the middle of a busy town!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on FOR LOVERS OF HISTORY and commented:

Ah, the castles of England…

LikeLike

Thank you for this. It filled in a missing piece for me: the Anglo-Saxon approach to defense. Find the right word to plug into a search engine–in this case, bush–and it’s amazing how much easier it is to find what you’re looking for.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s great to hear! It has been great to learn about these defenses from Simon, so much I had not thought about castles prior to the Normans!

LikeLiked by 1 person