Today’s post is a slight detour to my usual content in that it is far more of an opinion piece rather than about a particular historical event – but I hope you all enjoy it anyway! This year has seen a slew of historical-based films hit the cinemas, with many doing exceedingly well. Perhaps most famously of all, The Favourite won an Oscar, a Golden Globe, 7 BAFTAs, and, if Wikipedia is correct in its calculations, then in total it won 119 awards across various bodies. Clearly, there is a market for films like this, but the popularity of historical films this year such as Bohemian Rhapsody, Mary Queen of Scots, and the Green Book have raised many questions.

The Favourite centres on the rivalry between two female favourites of Queen Anne, who ruled Great Britain between 1702 and 1707.

The Favourite centres on the rivalry between two female favourites of Queen Anne, who ruled Great Britain between 1702 and 1707.

If you Google any of these films you will find hundreds of articles exploring the historical accuracy of them. The internet is filled with lists of the most historically inaccurate films. There is always a very vocal community who talk about historical accuracy of any period film or television show – in fact, this is an issue I have already explored in a post about the Colonial women of North America, in response to a criticism that the show was pushing liberal agenda at the cost of historical accuracy. Very often, those who are criticising the historical accuracy of films are those interested in history itself. I am part of a Facebook group of nearly 120,000 members who are interested in British Medieval History, and mentioning Braveheart is akin to the most severe swear word.

My feelings on historical accuracy in film and television are mixed, and so I thought it would be best to break this up into reasons for and against historical accuracy.

For

Historical accuracy is important if you are going to make a film that you are basing on history. If you are going to make a film about Elizabeth I and sell it as a historical biopic, then claiming that Elizabeth was in fact an alien sent to subjugate the English people to fight an intergalactic war is probably not the best way to go about it (but hey, I’m beginning to think that could make quite an interesting sci-fi film…). Certain films, like the hit Victoria and Abdul of 2017, are advertised with a level of authority that claims it is in fact meant to be pretty accurate, and so in this case adhering to the truth when possible should definitely be an aim.

For many members of the public, historical films and television shows are their gateway to information about a particular period. Most people stopped studying history by the time they were in their mid-teens, and so anything they did not learn at school will often be consumed via visual media, unless they find a particular interest in history and decide to read books and articles on the topic. For this reason, directors therefore owe a degree of loyalty to this fact, and playing with the truth can possibly mislead viewers.

Cartoon via The New Yorker.

One of my biggest personal reasons to champion historical accuracy in films is simply that history is FASCINATING. The stories that can be dug up can be absolutely mind-blowing, and it very much follows the adage that truth is stranger than fiction. On this blog alone I have talked about the medieval English queen who overthrew her husband and ruled for three years with her lover, about a 13th century monk who was not only having an affair with a woman AND her daughter, but who spent huge amounts of money hiring a sorcerer in order to find the body of his brother in the River Ouse, and two men at the court of Henry II who had a falling out over cake that was affecting the running of government. One need only read about the Court at Versailles, or life under Nazi occupation, or the Wars of the Roses to learn that history is filled with murder, intrigue, affairs, betrayals, and strong characters. When films stray from historical accuracy to make a ‘good’ story, I find it strange as I have read so many things in history books that have made me go “why isn’t this a film?!”.

Finally, although the popularity of historical dramas has increased in recent years, with series such as Victoria or the Crown in a long-term format of extended television series, for quite a while film and television of an entertaining nature (as opposed to documentaries) were either scarce, or limited to very particular eras (such as the unending plethora of films about the World Wars). For people interested in other parts of history, films that may focus on your time period or topic may come around once in a blue moon. If you love a particular period and want to see a creation of it in a fictional setting, then having a single film come out about it that you know is riddled with inaccuracies can be very frustrating and a let-down. By being more historically accurate, these films would therefore appeal to their target market far more.

Braveheart is often derided as one of the least historically accurate films.

Against

However, I argue that actually there are several reasons that we should stop nit-picking on historical accuracy. Whilst it can be understandable to complain about bigger issues in films, the level of some complaints can be farcical. In one article from 2017, The Guardian recounts how one viewer wrote to the Telegraph to complain about how one character on Howards End, broadcast on the BBC, had held a piece of toast and spread it with jam with a spoon. True, tiny blunders in television programmes like a hat being worn in 1874 that wasn’t in fashion until 1876 may provide those in-the-know with a feeling of superior knowledge, but in the grand scheme of things it really does very little to detract from the overall experience.

Whilst those who enjoy history want to see historically accurate portrayals of a topic they find interesting and want to see in a visual format, at the end of the day fiction always takes a dramatic licence. It must be remembered that these are supposed to be television dramas, or blockbuster films, and as such they do not have the same goals as a documentary. They are not *supposed* to be 100% infallible. They have an agenda, a perspective they want to put across, a feeling they want to instil in the audience, sometimes even a political message. This does not have to mean they are bad.

In this year’s hit Mary Queen of Scots, Gemma Chan, who is of Chinese ancestry, played Bess of Hardwick, a white person, in an example of colour-blind casting. Via Bustle.

One of my favourite (pardon the pun) things about The Favourite was that it was specifically advertised as a comedy, not just a historical film. I was in stitches throughout a good portion of the film, and the thing I think the film did best above all other parts of it was portraying a feeling. Queen Anne ruled a few decades after the decadent and raunchy Restoration Court of the late 17th century, and after her death the Georgian period began which saw fashion reach extraordinary new levels with gigantic wigs, dresses that couldn’t fit through doorways, and warring members of the Royal Family. This century was one of ridiculousness, and the film portrays that excellently. Monarchs who were surrounded by flatterers looking to earn favour, who had expansive royal palaces and could bedeck themselves in the most sumptuous furs, jewels, and clothing were always going to have some form of complex, and would easily be subject to their own whims and emotions. Thus, Olivia Colman yelling at a poor young boy to look at her, then yelling at him for looking at her, not only brings us a laugh but reveals the kind of situations that could well have happened.

Whilst Anne may not have kept 17 rabbits, and the Duke of Marlborough may or may not have had an interest in duck racing, throughout the film I got this overwhelming feeling that they had captured the essence of the Court at the time. People were ruthless in stepping over each other to get the highest positions. Food and luxury and wigs abounded. Politics and the monarch were intertwined. One could fall just as quick as they rose. In this way, the modern language used, the silly scenes, the unique way of filming, the comedic scene titles, all go towards producing a feeling of the time. Here, I think historical accuracy takes on a far less important role. Anyone can read a book and learn the facts about Queen Anne’s court, but you’d be hard-pressed to find another piece of visual media that puts across the atmosphere and life of the Court in such a successful way.

This then brings me on to my next point: films do not have to be a mirror of accuracy, but are instead an opening to historical fact. Whilst I argued in the “for” section that many people will learn about a period or a person for the first time through these films and tv shows, the mountain of articles produced about whether something is “accurate” or what the “real history” is behind something shows that there is a huge market for people wanting to know the real, historic truth. Clearly, after watching these films and tv shows, thousands of people are going online to learn more. How can we complain about that? People are inspired by watching these films – even Br*veheart – and then go on to learn about the real history and real people behind it. People learning more about history can only ever be a good thing.

The character of Aunt Juley, portrayed here by Tracey Ullman, was the subject of debate over her eating of toast on Howards End. Via The Guardian.

One big argument against total historical accuracy in film and tv comes in a double prong: in our lack of understanding of the past, and in the public’s understanding of the past. In reality, there are certain periods we know a huge deal about. But some basic things can still elude us. How exactly did people speak? What did words and accents sound like? What were people thinking and feeling at a particular time? What were their motivations? What objects would a peasant truly have owned? In this way, historical accuracy can never be achieved, because we do not know the truth about the past.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

One of the biggest problems facing those who wish to make historically accurate films, is the lack of knowledge of the general public. Although many members of the public do not know great amounts about particular time periods, they believe that they do. One of the skills of historical consultants to tv shows etc is to advise on what people *think* is true. This has become known as the Tiffany Problem. Coined by fantasy writer Jo Walton, the name originates from the complications of having a character in a historical book named Tiffany.

Many people feel that Tiffany is a modern name, popularised by the film Breakfast at Tiffany’s. In fact, Tiffany was a name used across history, including in the medieval period. It was a skewing of the Greek word Theophania, and the Christian feast of the Epiphany. Girls born on the 6th of January, the feast day, were often named some variant of the word which included Tiffany. However, if you gave regular old Joe Bloggs off the street a book set in the 14th century with a central character called Tiffany, you would be laughed away.

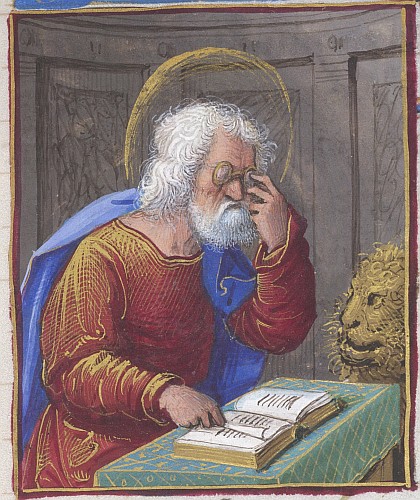

A film set during the medieval period may be scoffed at if it showed characters wearing glasses. However, as this miniature from a French manuscript dating to c. 1500 shows, glasses were indeed used at this time.

The legacy of the Tiffany effect can be seen in pretty much all history-based media pieces. One easy example is books. If you are watching a film set in the 18th or 19th century, your brain automatically says “everything is old”. Therefore, you expect people to be reading books that look at least somewhat aged. Bookcases may even seem somewhat dusty and worn. In reality, however, many of these books would have been absolutely brand new and freshly printed. There would be no wear-and-tear, no yellow pages or torn edges. However, you have someone reading a pristine book or newspaper that looks like it was made yesterday, people lose their immersion and feel that it is inaccurate.

Another example brings us back to that dreaded film, Braveheart. Many members of the public may be surprised to hear that kilts were not even invented at the time of the film, being invented over 400 years later. And the Scots certainly would not have entered battle covered in face paint, that most likely having ended around 1000 years prior. Whilst this is certainly a sore point for historians, for many members of the public these (the kilts particularly) are things that are associated with the old Highlanders of Scotland, and set the scene for them so that they can focus on more important details. For many, small historical inaccuracies are necessary to convince the public that they are actually portraying the period correctly.

In reality, the issue of historical accuracy in film and television is always going to be a sore subject, and not one that is ever going to leave heated debates behind. People are always going to have a huge range of opinions on the subject. At the end of the day, just like the subject matter and format, our views should be subjective. If a film is being released that is portraying itself as a true-to-life absolutely serious piece, then historical accuracy should have a very high priority, particularly as it is likely that the piece is being commissioned because it is intrinsically an interesting topic. If, however, more pieces like the Favourite come to the fore, or blind casting such as in Mary Queen of Scots takes more of a prominence outside of theatre, then historical accuracy can afford to go somewhat by the wayside. Here, it is the skill of the actors, the emotions being portrayed, and the atmosphere and feeling being given that are of far more importance.

Previous Blog Post: The Development of Castles in Britain (Part 1)

You may like: Fairy Tales or Medieval Reality? Historical origins of fantasy stories

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Excellent article – after a bit of a break I have returned to blogging and am especially looking forward to your historical insights. I got to get my own mind back into writing mode again too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks a lot! I have also had a bit of a break but finally have my schedule in order now so hope to be a bit more active on here. I look forwards to new posts from you too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

History, smistory! Entertainment is just that and if it makes a few people both to check the veracity of an event then it has fulfilled two functions ! Keep enjoying the films!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah very good point! We can all enjoy something if the only historical accuracy is the setting to provide a story

LikeLiked by 1 person