With winter well and truly settled in, many places have been experiencing snowfall. Some places in the UK narrowly missed out on having snow on Christmas Day, bringing a much-desired White Christmas. Snowflakes bring many people joy for their crisp, clean coating of the land. School children learn how to cut out snowflake shapes from paper for decorations, and people love to share the fact that every single snowflake is unique. This variety of shapes has long been a fascination of humanity, but did you know that the first ever photograph of a snowflake was taken all the way back in 1885?

In February 1865, a man called Wilson Bentley was born in Jericho, Vermont, USA, to farmer parents. At the time, the American Civil War was still not over and had torn the country apart, with hundreds of thousands dead. Being born into a farming family, Bentley could have been expected to continue in his family’s footsteps, working the land and making a living in the countryside. For farmers in his area of Vermont, winter was usually a difficult time, with average annual snowfall of around 120 inches. Snow, viewed as beautiful and harmless to many today, could make survival difficult, particularly in a time before modern conveniences like central heating and widespread use of electricity.

For Wilson Bentley, however, this hazardous snow was beautiful and fascinating. Later in life, Bentley would say “always, right from the beginning, it was the snowflakes that fascinated me most”. Knowing his interest in small things around him – not just snowflakes, but butterflies, spider webs, raindrops, and other natural phenomena – for his fifteenth birthday his mother gave him a microscope. His mother had been a teacher prior to marriage, and she had kept the microscope which she had used for school lessons. The microscope opened up a whole new world for Bentley, but it was still not enough for him to study his favoured snowflakes. He found that captured snowflakes would melt too quickly for him to properly study their ever-changing designs under the microscope. He needed something more permanent.

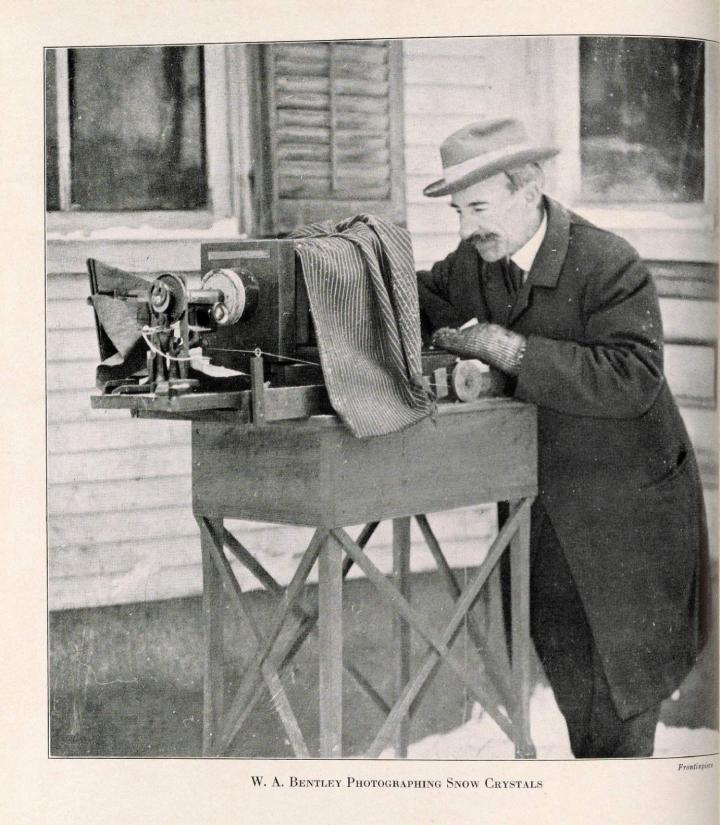

Bentley managed to get his hand on a camera, despite disapproval from his father, and he spent over a year experimenting with the camera and his microscope, learning how best to capture the tiny objects seen through the equipment. Photography and cameras were only a few decades old, and it could take minutes to take one photograph. When dealing with an ethereal, brief object like a quickly melting snowflake, this was too long. The first Kodak camera was not to go on sale for several more years. However, a young Bentley persevered with his craft and finally he came up with a system.

On the 15th January 1885, Bentley took his equipment out in the midst of a snowstorm. He connected his camera to his microscope and stood in the cold, catching falling snowflakes. When he found one, he gently lifted it with a feather so as not to melt it and placed it under the lens of the microscope. The freezing cold of the outside air allowed the snowflake to last through the minute and a half-long exposure to take a photograph. Instant photo printing was still a long way away, so Bentley took his film inside and developed the negatives. He almost fell to his knees: at last, he had managed to take a good photograph of a snowflake, resplendent before him. “It was the greatest moment of my life”.

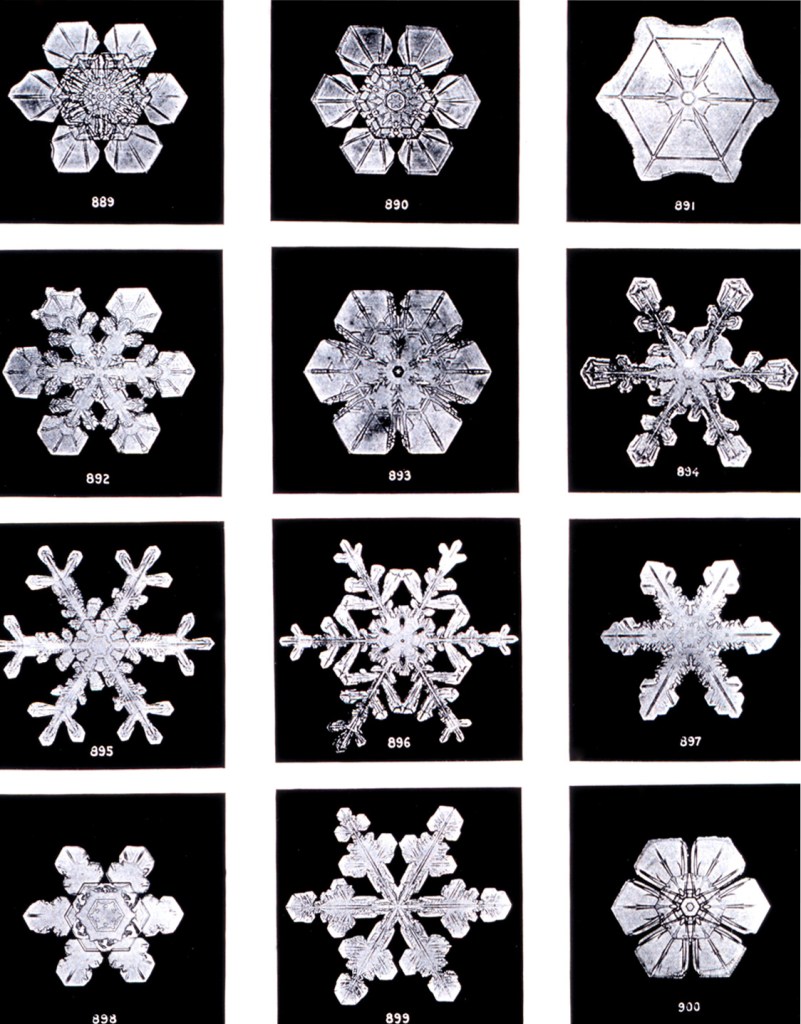

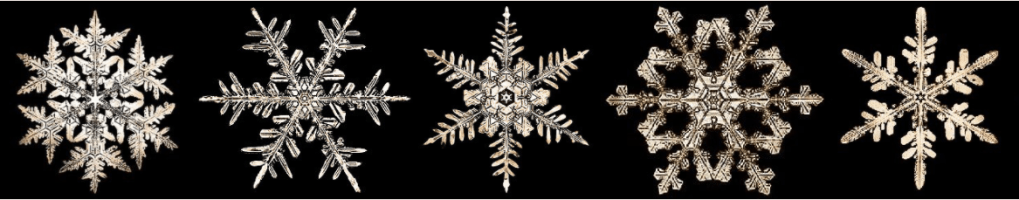

Bentley was truly a pioneer, the first known person in the world to have taken a detailed photograph of a snowflake. His success buoyed him to continue his mission, and he perfected his technique by catching the snowflakes on black velvet to better distinguish their unique features. For the next thirteen years he continued to photograph over 400 snowflakes. He studied them, recorded their features, and made the observation that no two of the snowflakes he had photographed were the same.

Despite Bentley’s incredibly important work, he stayed relatively obscure during this time. Being the son of a farmer, who had never been to school (having been home schooled by his mother), he did not realise how pioneering his work was. He figured that the hordes of intelligent people at universities and scientific institutes across the world must have already discovered his technique for themselves and had been doing their own studies. Eventually, word of Bentley’s project reached the University of Vermont and came to the attention of George Perkins. At that time, Perkins was the professor of natural history at the university and had been for close to two decades. Perkins realised the importance of Bentley’s work, and contacted him.

Perkin managed to convince Bentley that his work held great importance and needed to be shared, and so together the two of them drew up an article on his findings which was published in 1898. The article took the world by storm, particularly due to the ever-growing popularity of photography, and Bentley was encouraged to continue his studies and publish more articles. By the time of his death in 1931, he had taken more than 5,000 photographs of snowflakes. Bentley was not just a photographer, however, and he came up with many scientific theories to explain the form and structure of the snowflakes he came across. He suggested that different shapes were influenced by different air temperatures, and that different segments of a storm could produce their own types of crystals.

Although Bentley was to be known as Snowflake Bentley, he studied other aspects of meteorology. Vermont was not always under snow, after all. Towards the end of the century, Bentley began to study the origin of rain during the summer months. Again, Bentley discovered much previously unknown about rain, including the largest possible size of one raindrop and the idea that rain can be formed by two different processes.

The title page and one of the printed photograph pages from Bentley’s 1931 book, Snow Crystals.

For the rest of Bentley’s life, his incredible work continued to grab the attention of select scientists and the public alike, although the people who lived with him in Jericho never seemed to understand or appreciate his work. Other meteorologists also seemed to ignore much of Bentley’s work, perhaps looking down on him as an uneducated farmer. Realising the importance of his work over the past few decades, however, in 1904 Bentley donated 500 of his snowflake photographs to the Smithsonian Institution to ensure their survival for posterity. They are still there today.

By the 1920s, Bentley had shifted his attention to sharing his snowflakes with the wider world who seemed to have more interest in what he had created than the scientific community. Jewellers and the textile industry bought his photographs for design inspiration and he had gained his nickname as the Snowflake Man. Finally, in 1924, his work was recognised by the American Meteorological Society who gave him their first ever research grant in recognition of the 40 years of work he had put in to the discipline.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

By the 1930s, demand was growing for a definitive volume of Bentley’s work. He partnered with William Humphreys of the US Weather Bureau to create “Snow Crystals”, a book which contained nearly 2,500 of his photographs. The book was released in 1931, but Bentley did not live long past its publication. Now aged 66, he was still continuing his work. In December he went out in a snowstorm where he caught pneumonia. He died on 23rd December 1931.

The legacy that Wilson Bentley left behind would have made him proud. “Snow Crystals” is still in print today, and his home is on the USA’s National Register of Historic Places. His method of snowflake photography is little-changed today, and it has been said that his work was so excellent that for almost 100 years hardly anybody else bothered to try photographing snowflakes. Many of his meteorological theories, ignored at the time, have now been proven correct. Copies of his photographs and slides were given to many institutions, but the largest collection remain in his home town of Jericho, at their Historical Society. And his photographs remain as beautiful today as when he first captured them over 130 years ago.

Previous Blog Post: Empress Hermine: A Quotation Mark Empress

Previous in Historical Figures: Alice Chaucer, Lady of the Garter

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

https://siarchives.si.edu/history/featured-topics/stories/wilson-bentley-pioneering-photographer-snowflakes

https://snowflakebentley.com/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/the-man-who-revealed-hidden-structure-falling-snowflakes-106274664/

http://xray-exhibit.scs.illinois.edu/books/bentley.php

https://www.brainpickings.org/2020/01/19/wilson-bentley-snowflakes/

I spent a happy half hour contemplating the beauty of snow flakes inspired by this post. Thank you!❄️❄️❄️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aw that’s lovely! I really enjoyed writing it, seeing all the pictures are stunning and even more so knowing how old they are and yet how perfectly they capture the snowflakes

LikeLike

Very interesting article. Bentley was a hardworking and humble man. I’m glad he finally received recognition for his work. His snowflake photos are exquisite!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I am too. His work was incredible, particularly for the time he was doing it. And what gorgeous photos to survive!

LikeLike