If you’ve ever flicked through an illustrated medieval manuscript, or seen pictures of some marginalia on the internet, chances are you’ve seen pictures of snails. Sometimes the snails are fighting each other, sometimes they are fighting knights, sometimes things are riding the snails, but in one form or another, snails keep cropping up in these manuscripts. So, were the writers and illustrators of these manuscripts huge lovers of the snail, frustrated gardeners, or did the snails represent something deeper?

In short, we don’t really know. Numerous theories have been raised about what the snails could represent and why they are so prevalent, so I shall take you through some of them (and as the pictures are so oddly charming, this will be a picture heavy post!).

Knight defending himself and his wife, who holds a distaff, against a giant snail (Festal Missal, Amiens, 1323).

Knight with a club fighting against a huge snail (Smithfield Decretals, southern France, c. 1300 – c. 1340).

1) The snails represent death/the Resurrection

One of the first people to pick up on the strange addition of snails to manuscripts was Comte de Bastard in 1850. He noticed that in two manuscripts there were marginal snails very close to miniatures of the Raising of Lazarus (for those not aware, this is a Biblical story where Jesus brings Lazarus of Bethany back to life four days after his burial). This led Comte to theorise that the snails must represent the Resurrection – the two images must be linked.

Another suggestion tied to death comes from medievalist Lisa Spangenberg, who highlights another Biblical connection – Psalm 58. This is discussing the punishment of the wicked, saying “let them be like a snail which melts away as it goes, Like a stillborn child of a woman, that they may not see the sun”. This leads to the suggestion that the valorous knights are fighting the “wicked” who will eventually meet their just punishment.

(Above) A Knight losing against a giant snail (Ormesby Psalter, England, c. 1300).

(Below) A knight praying for help or begging for mercy against a snail (Gorleston Psalter, England, 1310 – 1324)

2) The snails represent the Lombards

Historian Lilian Randall has suggested that the snails represent the Lombards, a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774 AD. By the time that the snail marginalia start to become frequent (c. 13th century), the Lombards were an unpopular group in Europe, with the view that they monopolised jobs, lent money at unreasonable rates, and were overall a treasonous, sinning, un-chivalrous bunch. Placing them in marginalia serves as some xenophobic fun, and would account for why they are frequently shown fighting chivalrous knights – a sort of ‘good ideals vs bad ideals’. However, many have questioned this theory, as explained by the British Library: this “does not explain why the knight is often depicted on the losing end of this battle, or why this particular image became so popular in the margins of non-historical texts such as Psalters or Books of Hours”.

This time the snails are being ridden by naked jousters (Lectura super Institutionibus, France, 1480 – 1481).

This time the snails are being ridden by naked jousters (Lectura super Institutionibus, France, 1480 – 1481).

3) The snails are satire

Rather than showing the brave knights fighting off an evil foe such as the Lombards, there is an idea that the snails vs knights motif is a humorous satire on the knightly class and the idea of chivalry. Often in the pictures, the knights are shown as losing or cowering in terror. Snails are obviously an unworthy foe for a brave knight, and Elizabeth Moore Hunt has suggested that “the natural baseness of the animal makes it unworthy prey for splendid jousting gear and thus a humorous parody of the knight in arms”. Essentially, knights claim to be big and brave, but they only take on weak foe that they know they can beat, showing their true cowardice.

A cowering jousting knight (Li Livres dou Tresor, France, c. 1264).

A naked man begging for mercy at a snail (Gorleston Psalter, England, 1310 – 1324).

4) The snails represent social climbers / poor vs rich

There are numerous ideas that the snails vs knights are a clear commentary on social class struggles. The knights represent the higher levels of society, whereas the snails are the poor masses. They have no weapons with which to fight those above them, and they are base creatures struggling to win against those who have a better lot in life. Arguments against this idea and the idea of satire include the fact that it was exactly these upper classes who were commissioning these pieces, and would they want to be reminded of the oppressed poor, or be made fun of, in their own treasured books?

This leads to the idea that the snails represent social climbers – a significant worry to established families of old nobility. Concerns on social climbers, men who had come from nothing and were promoted by the king, are evident in most reigns of medieval monarchs. When your power comes from your proximity to the king and your ability to influence him, those viewed as social upstarts who have been promoted from nowhere were a real danger to your personal power and influence. This could be why so many of the scenes show the knight losing the battle – it was representative of the nobility’s feeling of powerless.

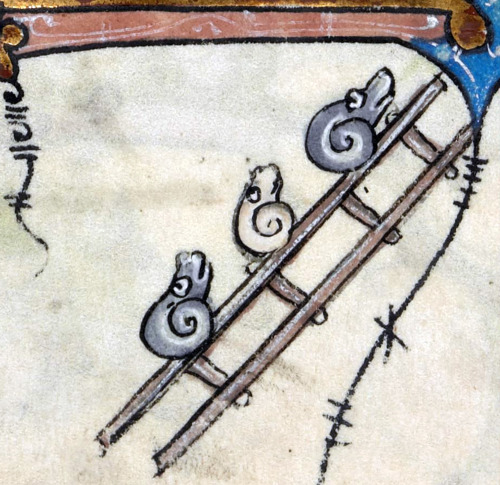

Lilian Randall’s survey includes several pictures where snails are climbing steps or ladders – a seemingly obvious metaphor for base social climbers.

Snails on a ladder (Hours of Saint-Omer, France, c. 1320).

5) It’s just a bit of fun

Instead of representing something deep and meaningful, the illustrations are much like modern-day comics, and are just a bit of fun. Much in the same way that we look at the pictures today with humour and intrigue, perhaps it was designed to serve the same purpose eight centuries ago. There are many weird creatures and silly pictures found in marginalia that often have nothing to do with the content of the text it was decorating, and perhaps snails were just another of a bunch. It is humorous to see a brave knight cowering in terror at a harmless snail!

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

A person throwing rocks at a giant snail (Smithfield Decretals, southern France, c. 1300 – 1340).

We will never know why the image of the snail was so popular or so prevalent in these medieval manuscripts. Crossing borders by featuring in French, English, and Flemish manuscripts, and found anywhere from 12th to 15th century pieces, the snails were an enduring symbol of something. It is likely its meaning changed over time and that spanning several centuries and different countries it probably represented all of these things at one time or another, and probably had other meanings to boot. One thing that is for sure is that centuries later, these pictures are still entertaining audiences across the globe.

I want to quickly mention that Just History Posts now has a Facebook page! If you want to stay up-to-date with blog posts, and learn other interesting snippets of history or about intriguing objects and buildings from across the world then please give us a like (and even share with friends!)

Previous Blog Post: Gunpowder, Treason, and Plot: Who was Guy Fawkes?

You may like: Medieval Reacts and Two Monks: History in Social Media

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

http://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2013/09/knight-v-snail.html

https://aleteia.org/2016/06/22/why-did-medieval-knights-fight-snails/

https://redditblog.com/2015/11/25/the-marginalized-art-of-snail-fighting-in-medieval-europe/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/why-were-medieval-knights-always-fighting-snails-1728888/

39 responses to “Medieval Marginalia: Why Are There So Many Snails In Medieval Manuscripts?”

Fascinating! Might have to share with my readers… and up my doodle game.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I find it so interesting that we have absolutely no clue what they might represent and all we can do is make educated guesses – and it certainly inspires you to doodle away!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes!! Love a good unsolvable mystery (and I’d wager you’re right that it’s probably a combination of all of the above). Weirdly, I’ve been doodling snails a lot lately in my diary on Wednesdays to denote the slllllllllllow passage of the week. They are certainly fun little creatures to draw … and now I might add a knight or too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a coincidence! You will definitely have to add some little knights now!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very, very weird and wonderful. Great post.

LikeLike

Thank you! I am glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike

The images are fascinating and I understand why people spend a lot of time trying to work out what they mean, but other marginalia are just as fantastic and beyond understanding. Sometimes I wonder if there isn’t a play on words in them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

They really are! But yes you are right, there is so much peculiar marginalia (which I hope to come back to in future posts) and whilst it can be frustrating that we will never know what they mean (if anything) I think it’s quite nice in a way that these manuscripts have these hundreds-of-years-old secrets locked up in them – like a little “in-joke” from those living centuries ago that we will never be privy to!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting post.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for reading as always!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Lenora's Culture Center and Foray into History.

LikeLike

[…] entries. Following a month of this personal trend, justhistoryposts happened to write a blog about medieval snail marginalia week before last, of all things! As he/she/it (I think she’s a she, I’m pretty sure, […]

LikeLike

[…] Previous Blog Post: Why Are There So Many Snails In Medieval Manuscripts? […]

LikeLike

Wow! I love this. Such varied ideas. I hope that snail offers that poor naked guy mercy.

LikeLike

Thank you! It was fun to research. Indeed – or if not mercy, at least a pair of trousers!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] people doing all manner of activities, and many, many animals. A few months ago, I wrote about why there are so many snails crawling the pages of medieval manuscripts. Today, we turn to […]

LikeLike

From my ecology courses days – slugs (snails without shells) could eat more grass on a pasture than grazing sheep. Slugs come out at night but eat massive amounts of grass leaving less for production of sheep meat or goat milk. Snails could have been public enemy number one as food production could be severely curtailed by all those slugs (snails).

LikeLike

Very interesting! Although snails are a bit of a menace to gardeners today, you don’t think of what a huge impact it could have in a medieval society. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

[…] https://justhistoryposts.wordpress.com/2017/11/13/medieval-marginalia-why-are-there-so-many-snails-i… […]

LikeLike

[…] plenty of drawings of cats licking their butts, and knights fighting snails. Just History Posts suggests that there are plenty of theories as to why there is an absurd number of snails in ancient art. One […]

LikeLike

[…] plenty of drawings of cats licking their butts, and knights fighting snails. Just History Posts suggests that there are plenty of theories as to why there is an absurd number of snails in ancient art. One […]

LikeLike

[…] plenty of drawings of cats licking their butts, and knights fighting snails. Just History Posts suggests that there are plenty of theories as to why there is an absurd number of snails in ancient art. One […]

LikeLike

[…] plenty of drawings of cats licking their butts, and knights fighting snails. Just History Posts suggests that there are plenty of theories as to why there is an absurd number of snails in ancient art. One […]

LikeLike

[…] plenty of drawings of cats licking their butts, and knights fighting snails. Just History Posts suggests that there are plenty of theories as to why there is an absurd number of snails in ancient art. One […]

LikeLike

[…] plenty of drawings of cats licking their butts, and knights fighting snails. Just History Posts suggests that there are plenty of theories as to why there is an absurd number of snails in ancient art. One […]

LikeLike

[…] plenty of drawings of cats licking their butts, and knights fighting snails. Just History Posts suggests that there are plenty of theories as to why there is an absurd number of snails in ancient art. One […]

LikeLike

[…] plenty of drawings of cats licking their butts, and knights fighting snails. Simply History Posts suggests that there are plenty of theories as to why there is an absurd number of snails in ancient art. One […]

LikeLike

[…] also plenty of depicts of cats licking their butts, and knights fighting snails. Just History Post suggests that there are plenty of hypothesis as to why there is an absurd number of snails in ancient art. […]

LikeLike

[…] plenty of drawings of cats licking their butts, and knights fighting snails. Just History Posts suggests that there are plenty of theories as to why there is an absurd number of snails in ancient art. One […]

LikeLike

[…] (Source: Just History Posts) […]

LikeLike

[…] One of the first people to pick up on the strange addition of snails to manuscripts was Comte de Bastard in 1850. He noticed that in two manuscripts there were marginal snails very close to miniatures of the Raising of Lazarus (for those not aware, this is a Biblical story where Jesus brings Lazarus of Bethany back to life four days after his burial). This led Comte to theorise that the snails must represent the Resurrection – the two images must be linked (Hollman, 2017). […]

LikeLike

An earlier comment touched on the idea that snails are simply delightful to draw. In particular—speaking as someone who is inordinately fond of doodling spirals (including snails)—the shape may be key to its popularity. After all, spirals are common in the abstract forms of ornamentation as well, and there aren’t many spiral land animals to choose from. Snails therefore bridge the abstract and the representational, aligning them with the broader architecture of medieval art. In any case, it’s a fun subject to think about.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, a very good point! Spirals are a natural doodling shape

LikeLike

Hi

Have you considered that at least in some instances the snail would represent a king or prince? In general the sovereign?

It was common knowledge in medieval times that a rare pigment used predominantly by royalty was made from snails https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tyrian_purple

Depicting a snail as someone with whom the hero fought might have been a way to avoid the wrath of the king/prince.

If the person on the illustration prays to the snail it might have been a way to show prayer to the king without annoying the church.

Kind regards,

Peter

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting theory! I admit I’m not sure how much it was used at this time in Western Europe where the manuscripts originate but it could certainly have been a factor

LikeLike

[…] vs Snail https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2013/09/knight-v-snail.html Medieval Marginalia: Why Are There So Many Snails In Medieval Manuscripts? […]

LikeLike

[…] Pour une bonne synthèse sur les différentes significations médiévales, voir https://justhistoryposts.com/2017/11/13/medieval-marginalia-why-are-there-so-many-snails-in-medieval… [33] Michael Camille, Image on the edge : the margins of medieval art, p 35 […]

LikeLike

[…] vs Snail https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2013/09/knight-v-snail.html Medieval Marginalia: Why Are There So Many Snails In Medieval Manuscripts? […]

LikeLike

[…] Medieval Marginalia: Why Are There So Many Snails In Medieval Manuscripts? […]

LikeLike