Samuel Pepys is perhaps one of the most famous English non-royals from the 17th century. He kept a daily diary for almost ten years from 1660, meaning he is a crucial source for Britain just after the restoration of the monarchy. He covered key historical events first-hand, such as the tragic Great Fire of London, but he is also a great source for social historians due to the detail with which he records his personal life, from affairs to kissing a dead queen. But who was Pepys, how did his diary survive, and why is he so well-known today?

Samuel Pepys was born in February 1633 in London. His father was a tailor and his mother was the daughter of a butcher, but he did have some notable relatives who served as Members of Parliament. His father’s cousin, Sir Richard Pepys, was even appointed Lord Chief Justice of Ireland in 1655. So, whilst Pepys could have been considered as having been born into a lower-class family, he certainly had connections to a level of power and wealth. Pepys was fortunate enough to attend school, and in 1650 he managed to get a place at the University of Cambridge through two scholarships granted by his school.

After Pepys finished his degree, he entered the household of his father’s cousin, Sir Edward Montagu, who later became the 1st Earl of Sandwich. Pepys’ familial connection here was to aid him a few years later, as just a month after Montagu’s elevation in 1660, Pepys was made Clerk of the Acts to the Navy Board which gave him an annual income of £350. He was an able worker, and over time he gained a reasonable amount of power and influence in his position.

In 1655, Pepys, then aged 22, married the fourteen-year-old Elisabeth de St Michel, the daughter of a French Roman Catholic convert and granddaughter of an Irish knight. Pepys and Elisabeth’s relationship was often a topic discussed in Pepys’ diary, and although their marriage had troubles it seems that Pepys cared deeply for Elisabeth. Two years after their marriage, Pepys underwent surgery to deal with bladder stones that he had suffered from since a child which caused him almost constant pain. The operation was hazardous, and it may possibly have left Pepys sterile as he never had children through his life. It did, however, relieve him of his bladder stones.

The year 1660 was a momentous one. King Charles I had been executed in 1649 after a bloody Civil War, and for the next 11 years England and Wales were under an Interregnum of rule by Parliament (and Oliver Cromwell) instead of a monarch. Scotland had declared Charles’ son King Charles II in 1649 after his execution, and supported attempts for Charles II’s restoration, whilst in Ireland Oliver Cromwell enacted a regime of brutal subjugation. In April and May 1660, Britain finally came together to agree to the return of Charles II to serve as king of Scotland, England, and Ireland. England once again had a monarch, and living in London, Pepys was at the centre of the action.

By chance, Samuel Pepys had decided on 1st January 1660 to start to keep a daily diary. His diary was filled with detail, from the time he got up in the morning, who he saw, his opinions on theatre, his personal relations, and significant contemporary events. Pepys was therefore perfectly poised to talk about Restoration London, and as an upper-middle class man with connections to those at court, he serves as an excellent insight into the time. He even accompanied his master, Montagu, on his voyage to the Netherlands to bring Charles II back to England. Pepys’ diary is considered a frank and honest (from his perspective) account of his life, for he clearly did not intend the diary to be read by anyone apart from himself – or certainly not in his lifetime.

Pepys’ professional life continued to rise through the 1660s. In 1665, the Second Anglo-Dutch War began, and with many of his colleagues busy elsewhere, Pepys undertook a great deal more responsibility. His hard work and competence paid off, and the same year he was made surveyor-general of victualling to oversee his plans to supply the British fleet, a position which gave him an extra £300 income a year. Pepys’ position in the organisation of the Navy gave him access to new and exotic goods, including tea. In 1660, after a meeting with high-level naval experts, Pepys “did send for a Cupp of Tee (a China drink) of which I never had drank before”. Pepys’ mention of drinking a cup of tea is the earliest known written reference to someone in England drinking a cup of tea. At the time, tea was extremely rare and expensive, and it was only after the arrival of Queen Catherine of Braganza, Charles II’s wife, that the drink was made popular in noble circles and spread throughout the country.

Pepys’ diary notably records great detail of his many affairs he had throughout the 1660s. Despite seeming to care deeply for his wife, he was a philanderer and had a particular weakness for his female domestic servants. He describes vividly an occasion in 1668 when his wife caught him with his hands underneath their servant’s dress, pleasuring the woman. He also describes fondling the breasts of another of his maids when she would dress him in the mornings. It is clear that Elisabeth did not approve of her husband’s behaviour, and the servant who she had caught in the act with Pepys was swiftly dismissed from service. As we only have Pepys’ side of the story, it is difficult to know whether his servants consented to his behaviour or if he was assaulting them – and it is also important to remember that even if they did grant consent, there was a big power imbalance between them which meant their consent could not be full.

It was not just living women that Pepys had encounters with. In 1669, on his birthday, Pepys took his wife and servants to Westminster Abbey to look at the open coffin of Catherine de Valois, who had been queen to Henry V in the early 1500s. Catherine’s body had been mummified over time, and her preserved body served as a tourist attraction to those with the money to pay to access it. Pepys was one such man, and he took full advantage of the opportunity: “I did kiss her mouth, reflecting upon it that I did kiss a Queen, and that this was my birth-day, 36 years old, that I did first kiss a Queen.”

Pepys often indulged in the arts, visiting the theatre – although he was not a great fan of his near-contemporary, William Shakespeare. He thought Midsummer Night’s Dream was “the most insipid, ridiculous play that I ever saw in my life” and that Twelfth Night was a “silly play and not relating at all to the name or day”. He did, however, enjoy Macbeth which he saw nine times (that we know of). Pepys was also very passionate about music, playing multiple instruments, composing his own music, and singing in numerous venues including Westminster Abbey.

On 31 May, 1669, Pepys wrote his last entry of his diary. He had become sickly from working long hours, and he thought he was losing his eyesight in part for the abundance of writing he was undertaking. Quite apart from all the writing he had to do for his job, his diary of over 9 years had incredibly racked up more than one million words. He sadly concluded that he should completely stop writing, only dictating to clerks in future.

The month following his last entry, Pepys and his wife went on holiday to France and the Low Countries, returning in October 1669. Elisabeth fell sick as they got home and died on 10th November. Pepys was filled with grief at his wife’s death, writing letters to his colleagues apologising for not attending meetings or replying to letters for 4 weeks after Elisabeth’s death because of the “sorrow and distraction I have been in”. He erected a monument to her in St Olave’s Church in London, and he never remarried – though he is believed to have had a long-term relationship with his housekeeper to whom he left many possessions and a £200 annuity in his will.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

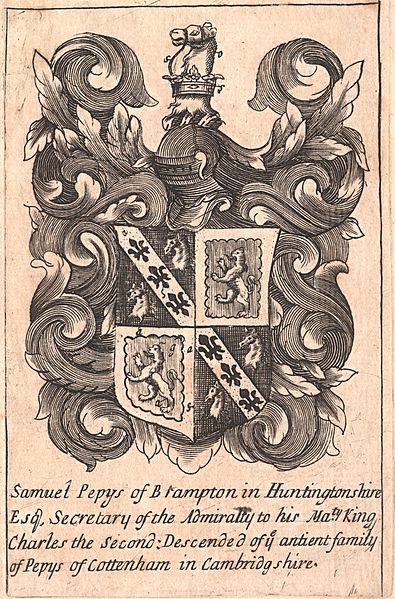

In the decades after the end of his diary, Samuel Pepys continued to work hard at his career: He was elected a Member of Parliament for various constituencies; he helped establish the Royal Mathematical School at Christ’s Hospital; he was made a Freeman of the City of London; he was appointed King’s Secretary for the affairs of the Admiralty; and he even had an island named after him (Pepys Island, which was probably a misidentification of the Falklands). Despite this, his life was not without hardship and in 1679 Pepys was arrested and imprisoned in the Tower of London under suspicion of piracy and treason. After some diligent investigation, Pepys managed to show that his accuser was a fraud, and he was eventually released from prison with the charges dropped.

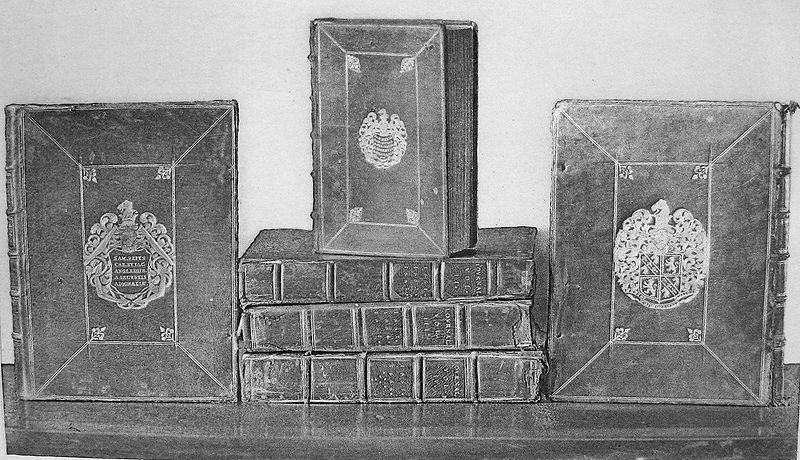

A decade later, in 1689 and 1690, he was imprisoned on suspicion of Jacobitism – supporting the senior branch of the House of Stuart after the overthrow of King James VII & II in favour of his daughter Mary II and her husband, William III. Although no charges were ever brought against him, Pepys decided at the age of 57 it was time to retire from public life. In 1701, he moved to Clapham – at the time part of the countryside – and he lived there until he died on 26th May 1703. As he had no children, he left his estate to his nephew. It was his wish to be buried next to his wife at St Olave’s Church in London, a wish which was carried out. In his will, he also left a collection of 3,000 books and manuscripts to Magdalene College, Cambridge, making it one of the most important surviving 17th-century private libraries. Within this donation were the six manuscripts of his diary.

Samuel Pepys’ diary remained at Magdalene College largely untouched until the 19th century. In 1818, the diary of John Evelyn – another 17th century diarist who lived at the same time as Pepys – was published, and this brought focus onto the diaries of Pepys. As Pepys had written in shorthand, various languages, and code, their remarkable content had been mostly unread. Between 1819 and 1822, a man named John Smith transcribed the diaries into plain English. Frustratingly, his task was made longer as he was not aware until he was nearly finished that Pepys’s library in fact held a key to the shorthand system just a few shelves away from the diaries.

Smiths’ transcription was the basis of the first published edition of Pepys’ diary which was released in two volumes in 1825. Several other versions were published through the 19th century, although Victorian sensibilities omitted the passages where Pepys described his sexual escapades. The first full, unedited edition was not published until 1970-83, where it was released in nine volumes. Interest in Pepys’ diary has only continued over time: in 2003, a website was created with the aim to publish, in real time, Pepys’ diary entries. It ran from January 2003 until May 2012, but its popularity has meant that the website continues to share entries from the diary today.

Samuel Pepys was a fascinating character, whose million-word, nine-year-long diary gives us remarkable insight to a man who lived over 300 years ago. Despite this distance, his detailed entries on his relationships, his sexual encounters, his work life, his leisure activities, and the greatest events of his day means that we can know him intimately in a way we know few others of his contemporaries. He rose from a reasonable, but somewhat obscure, background to the upper-middle class, gaining the confidence of nobility and kings, through which he was able to gain great insight to add to his diary pages. He fell foul of the law numerous times, although he always managed to escape unharmed, and left a legacy of writing – not only in his diaries, but in his huge library – that is not often rivalled in history.

Previous Blog Post: Women’s History Month 2021: Celebrating Female Historians (Part 2)

Previous in Historical Figures: Wilson Bentley, The Man Who Photographed Snowflakes

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

https://www.historyextra.com/period/stuart/samuel-pepys-diary-fire-london-cheese-facts/

https://www.magd.cam.ac.uk/pepys/samuel-pepys

https://www.pepysdiary.com/about/

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/samuel-pepys/

https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-21906?rskey=g1eXyU&result=6

8 responses to “Historical Figures: Samuel Pepys, Renowned Diarist”

Uh, “sexual encounters” and “affairs” misterm assault – since we’re unable to discern consent, there was a massive imbalance of power, and we only have his account – it’s impossible that all of those “encounters” were truly consensual. Might want to mention that. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hiya, thanks for your comment, I thought I had mentioned it but now I see I didn’t! I will add it in.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much! (and for the post – really interesting & fun to read)

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for highlighting I had forgotten it 🙂 glad you liked the post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Previous Blog Post: Historical Figures: Samuel Pepys, Renowned Diarist […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] parts of society. Some chocolate houses even charged an entry fee just to enter the premises. Samuel Pepys, renowned London diarist of the mid-17th century, wrote one of the earliest references to chocolate in England. In his […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve never read his diaries, but I recall an exhibition at at museum where one of his entries was quoted about burying cheese and wine in the backyard to keep it safe from the coming flames during the great fire….and thinking I like this man!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, an infamous story! Those items were very valuable then – and definitely relatable today!

LikeLiked by 1 person