Today starts a new series where we interview historians, museums, archives, students, writers, organisations, and anyone else connected to the history and heritage sector. There is a plethora of places to explore and people with in-depth knowledge about special subjects, and we look forwards to sharing our finds with you! If you or your organisation would like to be interviewed, then please leave a comment below, or contact our page via our Facebook or Twitter.

For this first post, we speak to Tess Wingard, a PhD student at the University of York, England, who you can find on twitter here. Her PhD looks at medieval ideas of sexuality in the context of animals and nature.

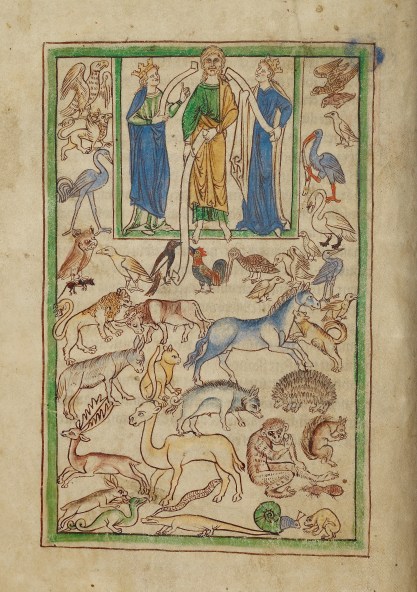

Adam naming the animals, from the Northumberland Bestiary c. 1250 – 1260, Ms. 100, fol. 5v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Programme.

Hi Tess! What attracted you to medieval history and why did you decide to do a PhD?

So, some scholars have tried to play up the similarities between the medieval and the modern periods, and this is definitely a valid approach in terms of helping us to get past a simplistic and inaccurate popular conception of “medieval = bad, barbaric, dirty, uncultured” and “modern = good, progressive, clean, cultured”. But what really attracted me to the middle ages, and this has been true since I was a small child, is how weird and alien it seems: ruined castles, manuscript illustrations, ways of thinking about the world that are completely different to how we think now. I had an undergrad module on medieval science taught by Dr Kathleen Walker-Meikle that really encouraged my interest in that area, and especially the study of animals.

As for why I chose to do a PhD? I hadn’t really thought seriously about it until I started writing my MA dissertation. The process of researching and writing a more serious sustained piece of academic work – especially the research I was fortunate enough to be able to do with manuscripts in Cambridge University Library and the British Library as part of this dissertation– made me realise that this was something I really wanted to do more of.

So tell us about your thesis, what is it about?

I explore the ways that medieval people (mainly in England and France between 1300-1500) thought about sexuality in terms of animals and concepts of nature and the boundary between animals and humans.

As an example – in earlier sources such as the Bestiary, you have stories about how animals such as partridges engage in homosexual intercourse. But in the 13th century, a philosopher such as Albertus Magnus comes along and says, “no, according to the writings of Aristotle and my own observations, all animals as a rule only have intercourse with others of the opposite sex and usually only with others of the same species, and humans – because we are capable of reason – are the only creatures that engage in sex with others of the same sex”. In this way, certain kinds of sexual behaviour – what we would now call ‘heterosexuality’ – become equated with ‘nature’ and ‘natural’ impulses and with animals, whereas other kinds of sex – what we would now call ‘homosexuality’ but which medieval people called ‘sodomy’ or ‘sin against nature’ – becomes regarded as something that only occurs in the human realm.

This takes us to some really interesting points where ‘scientific’ theories about animal sexuality are used to justify particular ethical or social stances. For instance, in the late 14th century in England, the Lollard movement pushed for a number of reforms to the practice of Christianity. One of these was that the practice of clerical celibacy – the rule that priests could not take wives – should be abolished because the authors of the Lollard reforms believed it encouraged priests to commit sodomy (or in other words, for priests to have sex with other men). One theologian, Roger Dymok, responded to this belief by saying that it was patently untrue according to knowledge of the natural world: animals, even if taken away from members of the opposite sex, never engaged in intercourse with members of the same sex. There was therefore no innate ‘impulse’ to have unnatural sex – and therefore, no grounds for abolishing clerical celibacy. So, my research really explores how all these ideas about sexuality, nature and animality are all interlinked through philosophical, legal and literary sources.

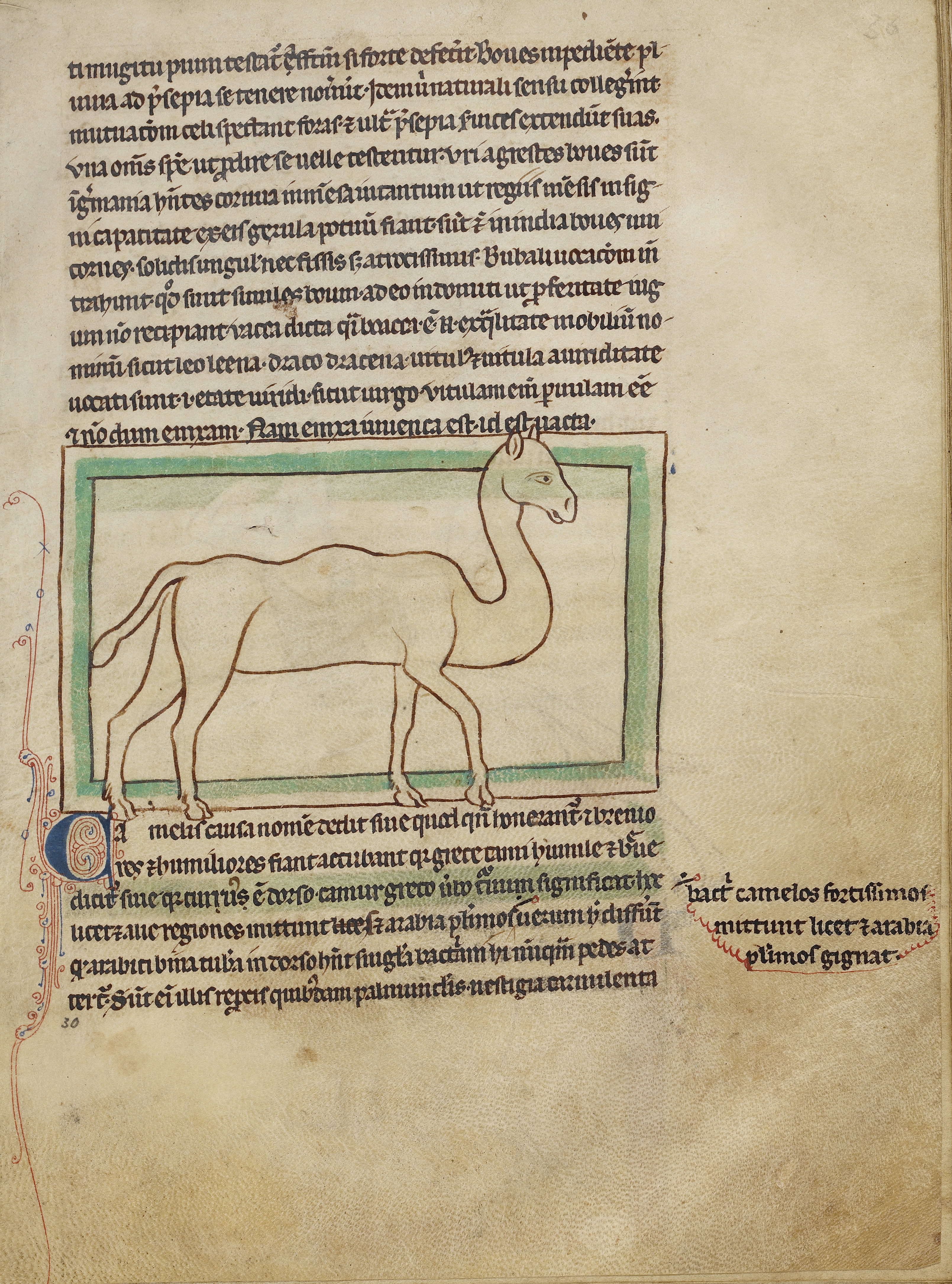

A camel from the Northumberland Bestiary c. 1250 – 1260. Ms. 100, fol. 30. Courtesy of Getty.

Wow, that’s really interesting! So where did you get the idea for it?

When I was first beginning to write my PhD proposal, on the advice of the people who would become my doctoral supervisors (Dr Nicola McDonald and Dr Jeremy Goldberg) I started reading about Lawrence v. Texas, the 2003 Supreme Court case which resulted in the nation-wide decriminalisation of sodomy in the US. One of the works cited as expert testimony was Bruce Bagemihl’s book Biological Exuberance, which synthesised a huge mass of zoological studies showing that over 450 different animal species had been observed as engaging in some form of same-sex intercourse or courting behaviour. Bagemihl and his supporters were saying, essentially, that because animals as well as humans engaged in homosexual behaviour, there are no grounds for calling homosexuality ‘unnatural’ and consequently we as a society should support the rights of LGBTQ people. Since then, “homosexuality is natural” has become an important mantra for the LGBTQ community. That got me thinking – if animals are so important to how we think about sexual morality in contemporary societies, is this true for the middle ages, when ideas about animals were radically different from how they are now?

So if both people today and the early Medieval period noticed plenty of examples of animals engaging in homosexual behaviour, why do you think there was a change later on to being convinced that only humans partook in it?

It’s mainly the result of classical texts being rediscovered, and new importance being put on certain authors. When Aristotle’s natural history texts were brought to Western Europe in the 12th century, philosophers really put a lot of emphasis on his ideas, one of which was that there were general principles of animal behaviour, including no homosexual sex. When Aristotle becomes influential to Western thinkers, his ideas take over previous ones, and he holds the main influence on Medieval ideas about animals until the 16th century.

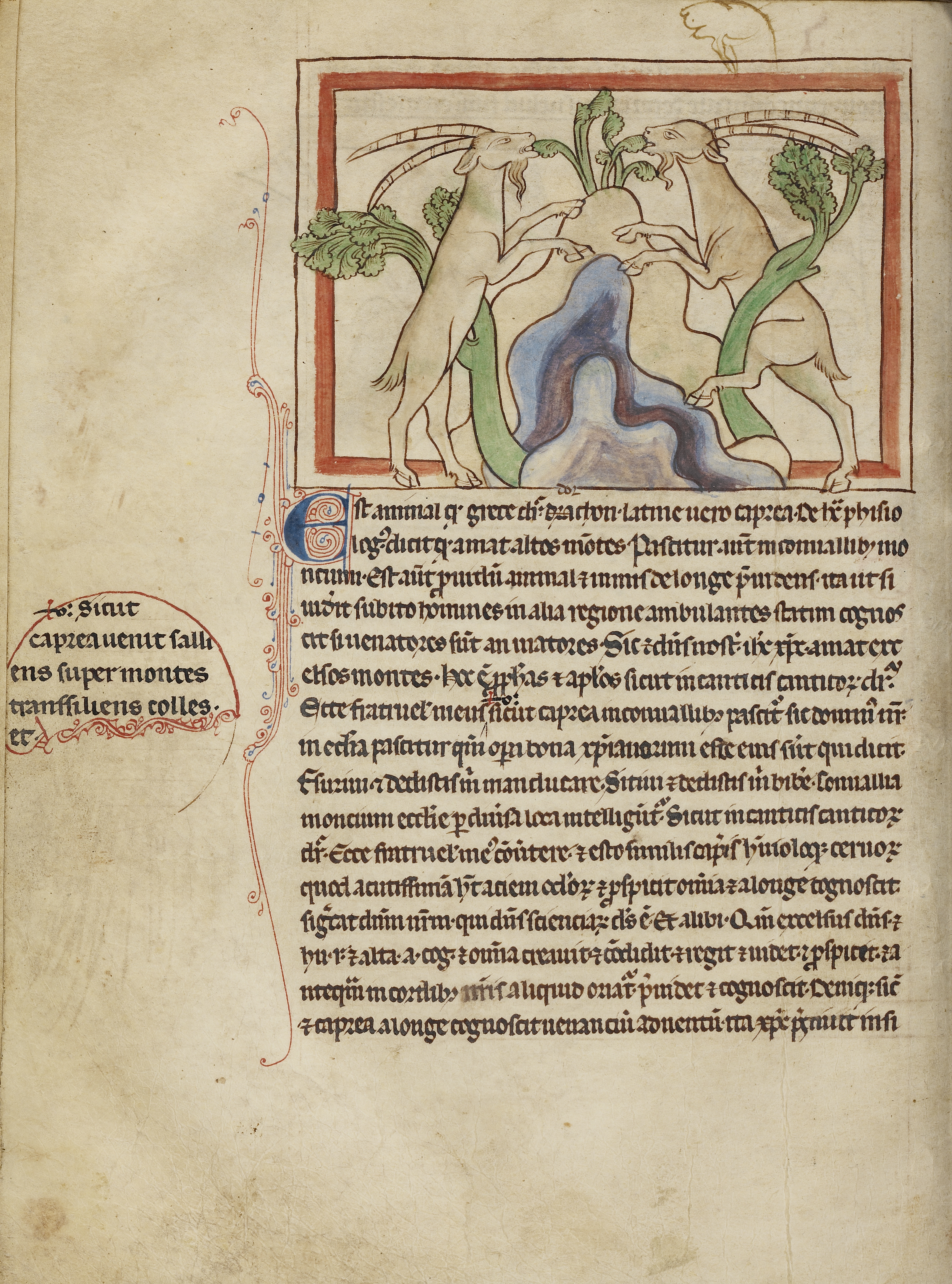

Two goats from the Northumberland Bestiary c. 1250 – 1260. Ms. 100, fol. 14v. Courtesy of Getty.

During your research, have you come across a source which you have found particularly special, interesting, or unique?

In 1364, Edward III issued a proclamation to the mayor of London informing him that he’d discovered a plot by a group of Londoners to kill an animal called an ‘oure’ (no-one seems quite sure what it actually was – it might have been a European bison or an aurochs) that had been introduced into the royal menagerie, apparently because they envied the beast’s zookeepers. Edward ordered the mayor and his sheriffs to keep the oure safe and to capture the plotters. I haven’t had the chance yet to go digging further to see if there’s any other relevant records, but it’s such a weird little incident that I can’t help but wonder what the bigger story was? You can read the proclamation here if you’re interested: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/memorials-london-life/pp315-320#h3-0006

That is certainly an intriguing event! Off the back of that, is there anything that you’ve found that has surprised you?

For me, the most surprising thing is how many medieval texts still haven’t been published, let alone translated. There are a fair few 14th and 15th century scientific texts which only exist in manuscripts, and so consequently they’re often overlooked in modern scholarship. I’d love to work on editing some of these in the future!

Ants from the Northumberland Bestiary c. 1250 – 1260. Ms. 100, fol. 23. Courtesy of Getty.

That is certainly a problem that many students and historians encounter – what has been your biggest challenge in completing your PhD?

I found my first year very stressful in terms of the number of commitments I’d signed up to. I was taking two language courses, a palaeography course and two subject modules, as well as a lot of extracurricular stuff. I just about managed to keep it all together, but if I could have gone back in time to the start of my PhD I would have definitely told myself to maybe commit to less straight off the bat. That same year, I was also learning how to navigate a long-distance relationship for the first time and coping with losing two grandparents in the space of a few months. Honestly, the first year was such a baptism by fire that the rest of the PhD has been fairly straightforward by comparison.

It certainly sounds like a challenging year. Do you have any advice for anyone who may be considering a PhD in Medieval history?

Make sure you pick a topic that you think you’ll be able to stay interested in continuously for at least 3-4 years. If you find that you’re already passionate enough about it to get into arguments about it, you’ve probably hit a good PhD subject.

Definitely great advice there. What are your plans for your next steps? Would you ever want to return to this topic area?

I’m hoping to stay on in academia and am trying my hardest to work on improving my chances in this respect, though I know the job market is incredibly competitive and it’s not easy to make a career out of medieval history at this point in time. I recognise that I have a lot of privilege in being able to cope with what may end up being an extended period of precarious employment and many of my colleagues aren’t so lucky – I guess I feel that if I’m ever going to give it a try, now is as good a time as ever in my life to try and pursue my dream.

In terms of topic area, I’d like to stay within the field of medieval animal studies. There’s still a lot of underexplored texts, authors and collections of archival material that I’d like to look at, and it’s a subfield which is still quite young within medieval studies, so I hopefully have the potential to write on subjects which people haven’t really explored before.

Two hedgehogs from the Northumberland Bestiary c. 1250 – 1260. Ms. 100, fol. 10. Courtesy of Getty.

A huge thank you to Tess for agreeing to be our first interviewee, and for sharing her fascinating research with us. If you want to learn more about this area of history, Tess has suggested some further reading which you can find below. And once again, if you would be interested in being interviewed – it doesn’t matter what aspect of history you are involved in! – we would love to hear from you, and you can contact us via our Facebook or Twitter below.

Previous Blog Post: Historical Figures: Ada Lovelace, The First Computer Programmer

You may like: Medieval Marginalia: At It Like Rabbits

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

https://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/ The Aberdeen Bestiary, dating to c. 1200 is considered one of the best examples of its type due to its lavish and costly illuminations. The manuscript can be explored for free from here.

https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/pwh/index-med.asp#c7 People with a History: An Online Guide to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Trans* History, Fordham University. This has an interesting medieval section with some open access articles and translated original sources.

4 responses to “An Interview With: Tess Wingard – Medieval Sexuality and Animals”

Very interesting

LikeLike

Thanks! Glad you enjoyed

LikeLike

[…] Previous Blog Post: An Interview With: Tim Wingard – Medieval Sexuality and Animals […]

LikeLike

[…] Previous in An Interview With: Tim Wingard – Medieval Sexuality and Animals […]

LikeLike