The pages of medieval manuscripts might be something that sounds very boring, but for those in the know, they read more like fantastical comic books. Pages upon pages of doodles in the margins showing imaginary creatures, hybrid animals, people doing all manner of activities, and many, many animals. A few months ago, I wrote about why there are so many snails crawling the pages of medieval manuscripts. Today, we turn to rabbits.

In traditional medieval symbolism, rabbits were generally good or harmless creatures. They represented purity and helplessness, often being tied to images of Christ. Sometimes they represented cowardice, due to their propensity to bolt at the first signs of potential trouble. Finally, they could represent fertility – just like a cockerel can be a term for a male body part, in the medieval period the Anglo-French and Spanish adjusted their word for rabbit into a term for the female body part. Probably for the same reason we liken rabbits to hot-and-heavy people today; rabbits breed, a lot.

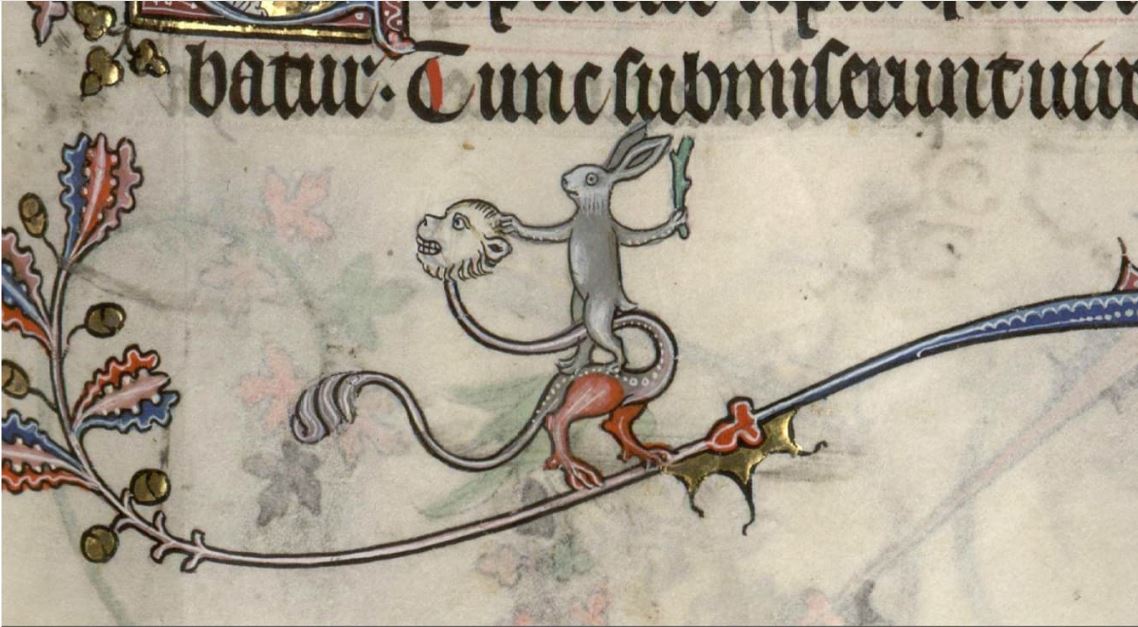

In the doodle margins of manuscripts where anything went, however, rabbits often transformed into violent, murderous creatures (like, seriously, there is some graphic stuff in here!). So what are the reasons for this transformation? Unlike snails, there seems to be far more unity in what they represent, but I’ll go through a few theories (with lots of pictures to boot).

Ms 107, Bréviaire de Renaud de Bar (1302-1304), fol.-89r-108r, Bibliothèque de Verdun.

Ms 107, Bréviaire de Renaud de Bar (1302-1304), fol.-89r-89r, Bibliothèque de Verdun.

1) The rabbits are a playful monde renversé (upside-down world)

By far the most universal explanation for the roles rabbits play in these marginalia is that it is a typical medieval trope of role-reversal used for humour. Throughout these doodles, creatures and humans alike are often portrayed as if the world were ‘upside-down’ – hunters being chased by their prey, brave knights being chased by snails… rabbits were a huge source of food and pelts for medieval Europeans, and so the humour is seeing the rabbits return the favour in these pictures.

Sometimes this role reversal is rather charming, with rabbits doing typically human tasks – conducting a funeral procession, or playing some music…

Gorleston Psalter, 14th century, f. 164r: detail of a marginal scene of rabbits conducting a funeral procession.

Gorleston Psalter, 14th century, f. 106v: detail of a marginal scene of a rabbit and another animal playing music.

… but often it is far more sinister, with the appearance of the murderous rabbits. Instead of rabbits being the ones who are hunted and killed, now it is the rabbits’ turn to hunt down those pesky humans. And as mentioned, this often has gruesome results….

The Smithfield Decretals, 1300.

This rabbit has hanged a hunting dog. British Library’s MS royal 10 E IV.

This idea of an upside-down world was one familiar to medieval people, not just through images in their books, but in celebrations in the physical world. There were several customs in the medieval period that used the upside-down world as its trope. One such was the custom of a ‘boy bishop’ which was commonly held on the feast of Holy Innocents (remembering Herod’s massacre of babies) or the Feast of Fools. A boy was chosen, perhaps from the cathedral choristers, and they would parody the real bishop, being dressed in full bishop’s robes, being attended by boys dressed as priests, and performing ceremonies and offices (except mass). The rabbits getting their ‘revenge’ on humans or hunting dogs was a continuation of this theme.

Paris, Bibl. de la Sorbonne, ms. 0121, f. 023.

Paris, Bibl. de la Sorbonne, ms. 0121, f. 023.

2) The rabbits represent the stupidity of the human in the text or image

Linked to the previous theory, some people take this as a very literal interpretation; one would have to be very stupid to be caught by a rabbit, and so the person in the picture must be a fool. ‘Stickhare’ was a Middle English name for cowards, and in many of these marginalia the rabbits are attacking humans with huge sticks, or have impaled them on sticks. Taking a nice literal meaning.

In this way, the marginalia actually leaps off the page and enters more physical representations. In Manchester Cathedral, there are a series of woodcarvings that were carved into the underside of the quire stalls, or ‘misericords’. Many depict a moral, and in these misericords we find some of these pesky rabbits. One particular one from the fifteenth century shows a hunter being spitroasted by rabbits who are also boiling his hunting dogs in a pot. This is very similar to the images seen in marginalia. Clearly, it was imagery that an ordinary person was expected to understand. Perhaps it was indeed a warning not to be a fool.

Misericord from Manchester Cathedral showing the rabbits cooking the hunter and his dogs. Source.

Rabbits beating a man with a stick and skinning him. Source unknown.

3) Subversiveness

Most of these marginalia were drawn by religious men, as they were the main bulk of the literature population. Books were often religious or historical texts, and the men mostly didn’t have the freedom to write the content of the text they were writing – they were simply copying out pre-existing books. This was boring, and the subject matter could be as well, and so the marginalia came out of a place of freedom of design, with the illustrations usually having nothing to do with the content of the pages they were on. The marginalia – and crazy rabbits – were a way for these religious men to explore ideas about society, critiquing or ridiculing it in safety by hiding behind fantastical creatures or strange scenes.

Ms 107, Bréviaire de Renaud de Bar (1302-1304), fol.-89r-137v, Bibliothèque de Verdun.

4) I don’t even know

BL Yates Thompson 8 f. 294r.

If you can read this article, and the post about the meaning of snails, and tell me what the meaning of this bizarre image could be, then please share! (In all seriousness, though, this links to the last ‘meaning’ in the snails post – the marginalia is just a bit of fun, and in the same way we look at the images today and laugh, perhaps that is all they were intended to do hundreds of years ago; be a bit of humour)

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

Vincent of Beauvais, Speculum historiale, France ca. 1294-1297 Boulogne-sur-Mer, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 130II, fol. 87v.

Rabbits are portrayed in a far more uniform way than some of the other marginalia, and the fact that they so commonly appear attacking or hunting men or dogs, means it is fairly agreed-upon that these images of rabbits are intended to be some humorous role-reversal of the real world, where rabbits finally take their revenge against those who hunt and eat them in real life. But as with any medieval image that appears in various countries across several centuries, there is never going to be one uniform meaning that covers all of the pictures. So for now, we can come up with theories, and just enjoy these murderous, fuzzy creatures.

Previous Blog Post: Women of Just History Posts: International Women’s Day 2018

Previous in Medieval Marginalia: Why Are There So Many Snails In Medieval Manuscripts?

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

Why Are There Violent Rabbits In The Margins Of Medieval Manuscripts?

http://www.gotmedieval.com/2010/08/eat-rabbit-justice-hound.html

It’s not that I’ve never looked at the marginal drawings in medieval manuscripts, but I’ve never looked at them like this, or given them much thought. You’ve made me see them differently. It sounds like there was a whole ‘nother story going on parallel to the text. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Yes it certainly is another world once you look past the text. What great little things can be found..

LikeLiked by 1 person

One more thought: I followed you on WP, which I never bother to check, so I hardly see your posts. If you’d add a button allowing people to follow via email, I’d much rather do that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! I have a button for following via email on the sidebar of posts (when you look via my actual website rather than the wordpress reader). I’ve been trying to figure out how to add a follow by email button on the bottom of my posts but I haven’t been able to find a way so far!

LikeLike

I’m on the actual website and all I’m finding is the follow button with th W–the WP reader button. It’s right by the Twitter and Facebook logos.

LikeLike

Gosh how frustrating! I want people to be able to sign up by email easily but wordpress doesnt seem to have an easy link that I can copy and paste into posts for people. If you scroll right to the bottom of the page, to the black footer bar, there should be a thing that says “follow me by email” and the link should be there. I shall do more research into how to make it easier to sign up!

LikeLike

Hi Ellen, I have finally found a way to add the email subscription button into the actual text – now if you open any of my blog posts and scroll to the end of the article, there should be a section where I suggest other posts to read, and a “follow me” section with a facebook and twitter icon, and now below it should be a box that allows you to subscribe via email. Please let me know if you find it and it works so I can confirm that I don’t need to do any more tech wizardry! All the best.

LikeLike