Today, many people have very staunchly held beliefs on medicine and cures for all sorts of ailments. Some people rigidly champion ‘western’ medicine, only believing in the effectiveness of drugs prescribed by doctors, usually in the form of man-made pills. Others go for the ‘alternative’ medicine route, preferring to use natural products in the form of plants and crystals, deciding that factory produced medicine can’t be good for the body. Whatever your beliefs, it is probable that you would agree that you were glad you didn’t have to use medicine in the past. It is well known that there were many gruesome or unappetising solutions to medical problems in the past, such as bleeding by leeches, or eating ground up mice brains. Whilst it is true that the medicine we are surrounded by today is leaps and bounds from that which people used a thousand years ago, you may be surprised to know that there are quite a few medieval treatments that aren’t too far from what we use today.

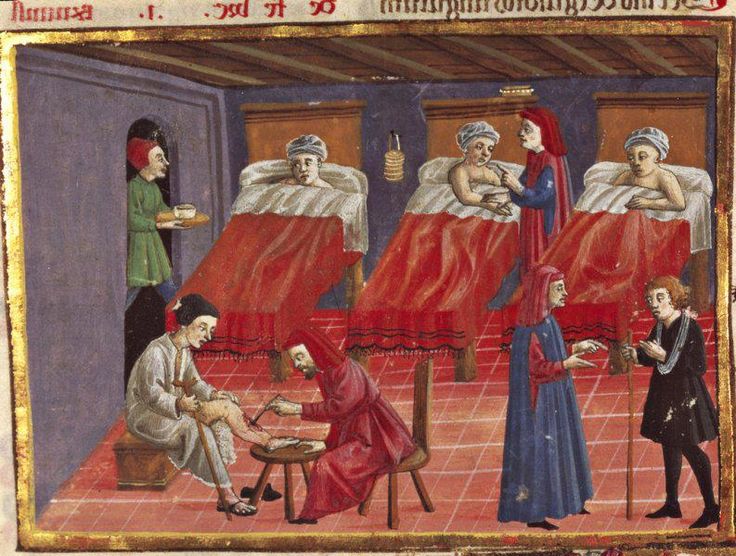

Patients being treated in an image from a c.1450 copy of The Canon of Medicine, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Firenze.

Perhaps one of the most famous medieval treatments was that of blood-letting using leeches or by cutting the skin. The basis for this treatment came from Ancient Greek theories of the ‘four humours’ that controlled human emotions, moods, and health. The four humours consisted of blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm (they were also sometimes categorised by the four elements; earth, fire, air, water). It was believed that if the four humours were out of balance, then you could be affected in different ways. For example, if you had an excess of yellow bile then you would be aggressive, whilst an excess of black bile was the cause of depression. Today we still use the word “sanguine” to mean optimistic or positive, and this came from the four humours. To even out the imbalanced temperaments, various treatments could be employed, including, for medieval audiences, blood-letting. By getting rid of “excess” blood, a whole range of maladies were believed to be cured, from fevers to plague.

Leeches were a usual go-to to perform this, for obvious reason, but people could just be cut and bled into buckets – it was believed to be beneficial to be bled until you passed out! Whilst today we do not tend to bleed patients (though it is still used for some blood conditions, usually to do with having too much iron or too many red blood cells), leeches are still a common tool used in hospitals. The leeches are, of course, disinfected and not just plucked from the nearest river, but the anticoagulant that they secrete whilst feeding is useful when doctors need to stimulate blood flow to damaged parts of the body, or to reduce the risk of blood clots. Leeches also naturally create an anaesthetic, meaning the patient does not have to feel the treatment. Moreover, the incisions that the leeches make are small and rarely scar. So, whilst we may not use leeches for the same reason as people did in the past, their use in medicine is still helpful enough to still be used today.

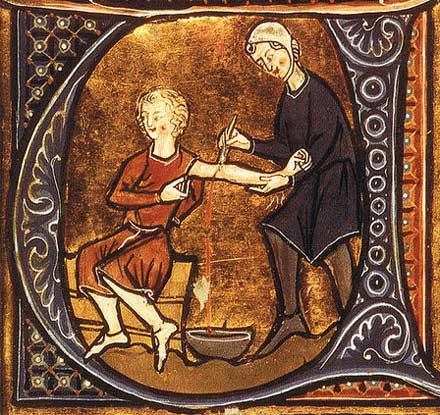

A miniature image of blood letting inside a letter from a manuscript c. 1500. British Library.

Another gross bug-related medical treatment involves the use of maggots. There is evidence that as far back as antiquity people may have wrapped a handful of maggots in a cloth and apply it to a wound to prevent gangrene – maggots only eat dead flesh, ignoring healthy, live tissue, and so it was a way to prevent the spread of infection in a wound. Today, maggot therapy is still used to clear out dead tissue and prevent infection for a variety of things, particularly ulcers.

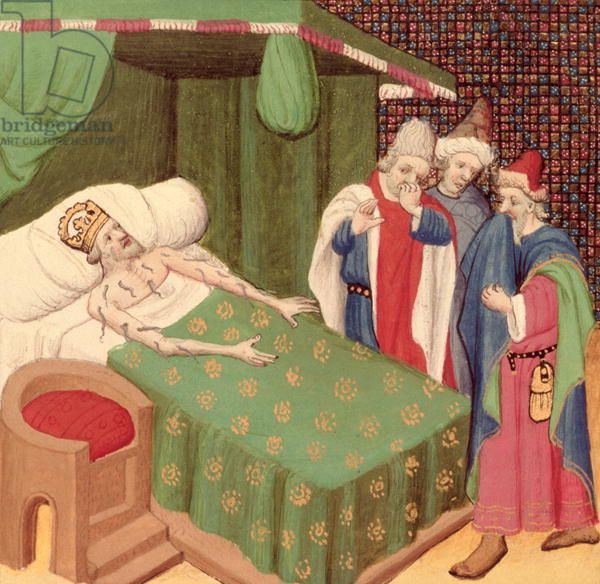

A king covered in leeches, Ms Fr 226 The Use of Leeches, from ‘The Decameron’, by Giovanni (fourteenth century).

Now, to move away somewhat from icky bugs! In 2015 there was lots of excitement in news outlets after scientists at the University of Nottingham recreated a 1000 year old Anglo-Saxon remedy for eye infections. The treatment was simple, using garlic, onion or leeks, wine and cow bile. The scientists claimed that they used the recreated treatment on MRSA – a dangerous modern super-bug that is resistant to most antibiotics – and the salve destroyed 90% of the bacteria. Whilst there is scepticism about the results, there is a fairly popular branch of medicine that is dedicated to recreating centuries old treatments and seeing if they have any useful applications to our modern medical problems. As with the leeches, whilst the concoctions may not actually help cure the problem it was intended, often medieval medicines do have useful properties in tackling pain and infection.

This should be no surprise, of course – why would people continue to use something if it never worked? Whilst our ancestors may have sometimes had incorrect theories on the workings of the body and diseases, they were surrounded by plants with medicinal qualities. It is easy for us today to forget that many of the medicines we use come from plants just because we ingest them in a manufactured tablet. Medieval people just had to go directly to the source!

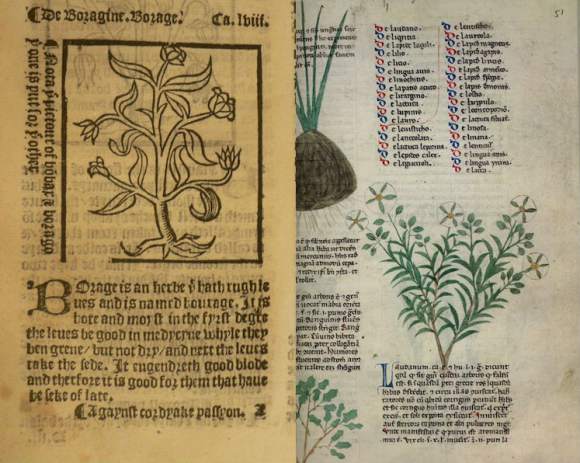

Pages from the Tractatus de herbis, a thirteenth-century book on herbal remedies.

Another treatment that goes back to well before the medieval period is the process of trepanation, or, drilling holes into the skull. Originally, it was probably believed that drilling holes into the skull released evil spirits trapped inside a person, but even in the medieval period it was used as a method to relieve severe headaches and epilepsy. Whilst it may seem counter-intuitive to drill a hole in your skull to relieve a headache, there is logic behind this that means that trepanation is still used today. Drilling a hole into the skull relieves pressure in the brain, meaning it is an invaluable treatment after severe trauma to the brain.

A depiction of trepanation by Guido da Vigevano, a 14th century Italian physician, and a 3,500 year old skull of a girl who survived the procedure.

We also have this picture today that people in the medieval period were filthy and unhygienic, and this is what caused a lot of their illnesses. Whilst in certain respects this is true, and medieval people had no idea about bacteria causing illnesses, they were not completely oblivious to the importance of cleanliness to public health, and they were not content to live in squalor. The English Parliament passed its first law requiring people to keep the streets and rivers clean in 1388, and contrary to popular belief, medieval people did wash – many towns had bath houses. By the thirteenth-century there were over 32 bathhouses in Paris, whilst in Southwark, in this period a separate town on the opposite side of the River Thames from London, there were 18 public hot baths.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

Whilst many people may remember being taught at school the claim that Elizabeth I thought she was hygienic for bathing “once a month, whether she needs it or not”, earlier medieval monarchs certainly took pride in their personal hygiene. When King John travelled around his kingdom, he took a bathtub with him, whilst in 1351 Edward III paid for taps of hot and cold water to supply his bathtub at Westminster Palace. Monasteries also often had running water and good toilet facilities, and many religious institutions built hospitals to serve the community. Many towns also had quarantine laws, most prominently used during times of plague, where they would board up the houses of plague victims, and isolate people with leprosy in ‘lazar houses’.

Two women bathing in private individual tubs, a privilege reserved for the rich.

So, whilst I am not trying to sell the medieval period as one of great, unquestionable hygiene, with medical marvels galore, there were certainly many aspects of medicine that continue in one form or another today. That, and that, despite Blackadder’s suggestions otherwise, the peasants may not have in fact been revolting!

Previous Blog Post: Medieval Dating Tips; or, How to Bag Yourself an Eligible Lord or Lady

Previous in Miscellaneous: Medieval Squabbles: Modern Relatability to the Medieval Royal Court

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Some sources used:

Interesting post on Medieval medicine. Especially love the pics!

LikeLike

Thank you! I’m glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

its good

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed!

LikeLike