Although people living in medieval Europe knew a lot more of the wider world than many initially think, with strong trade links in Asia and northern Africa, they were still intrigued about what lay beyond the land known to man, and stories of mythical creatures abounded. One such creature which fascinated for centuries was the Blemmy (spelt variously as Blemmy, Blemmyes, Blemmyae). These creatures were said to be a type of man who lived in Africa but they did not have a head – rather, their face appeared on their chest, their shoulders above them.

A Blemmy is seen on the left of this illustration from the Livre de merveilles, Paris, c1410. Wikicommons.

The Blemmyes were in fact a real African people, forming a nomadic kingdom in northern Nubia between 600BC and 300AD. Even from their early origins, however, stories were told of their headless nature. Herodotus who lived between 484 and 425BC wrote in his Histories that they were known as the akephaloi or those “without a head” and that they lived on the eastern edge of Libya. A few centuries later in c. 45AD Mela, a Roman geographer, wrote that the Blemyae lived in Africa and had their faces in their chests, and this was confirmed by Pliny the Elder who said the tribe had “no heads, their mouths and eyes being seated in their breasts” and located them in Ethiopia or Nubia.

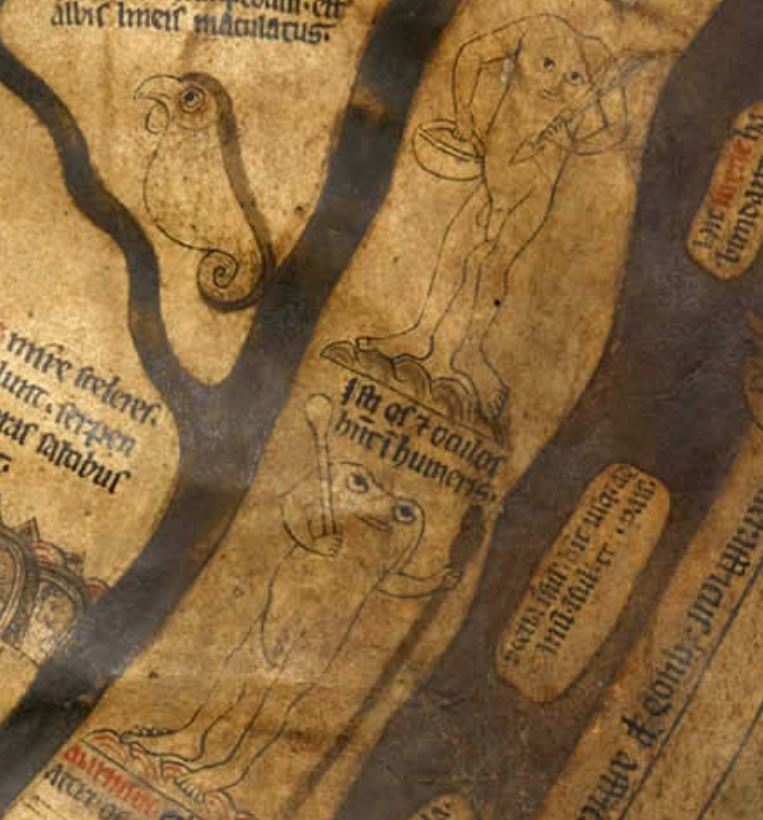

Blemmyes and other creatures from the Bird Book of Hugo Fouilloy, c.1280. WikiCommons.

The stories of these strange headless men continued long after the real Blemmye tribe was gone. In medieval Europe, drawings of these creatures can be found in manuscripts and in the extremities of world maps, charting the “unknown”. A drawing of a Blemmy features in an Anglo-Saxon manuscript in the British Library dating to c.1025, and Blemmyes are also found on the Hereford Mappa Mundi of 1300, the largest medieval map to still exist. Isidore of Seville (560 – 636 AD) explains in his Etymologies: “People believe that, in Libya, Blemmyae are born as trunks, without heads, and have their mouth and eyes on their chest. Others, born without necks, have their eyes on their shoulders”

The Blemmy in the 11th century Anglo-Saxon miscellany, British Library, Cotton MS Tiberius B V/1

Blemmyes on the Hereford Mappa Mundi, c.1300, via WikiCommons.

Blemmyes on the Hereford Mappa Mundi, c.1300, via WikiCommons.

As the centuries progressed, stories of the Blemmyes continued, and they moved with the boundaries of exploration. In the late medieval period, some are shown as being in India, such as on the 1436 Andrea Bianco map. As the sixteenth century arrived and the “discovery” of the Americas began, the Blemmyes moved across the seas. Ottoman admiral Piri Reis placed a Blemmy on his 1513 world map near the coast of Brazil and put a description next to the drawing. He said that Blemmyes grew to around 5’ 3”, their eyes were close together, but that they were harmless.

A misericord in Ripon Cathedral dating to the 15th century. WikiCommons.

In 1596, Sir Walter Raleigh wrote a book about his journey to Guayana where he reports that there was “a nation of people whose heades appeare not aboue their shoulders” who “are reported to haue their eyes in their shoulders and their mouths in the middle of their breasts and that a long train of haire groweth backward betwen their shoulders”. Although Raleigh did not see these people for himself, he decided that the stories were truthful as everyone he met there confirmed it.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

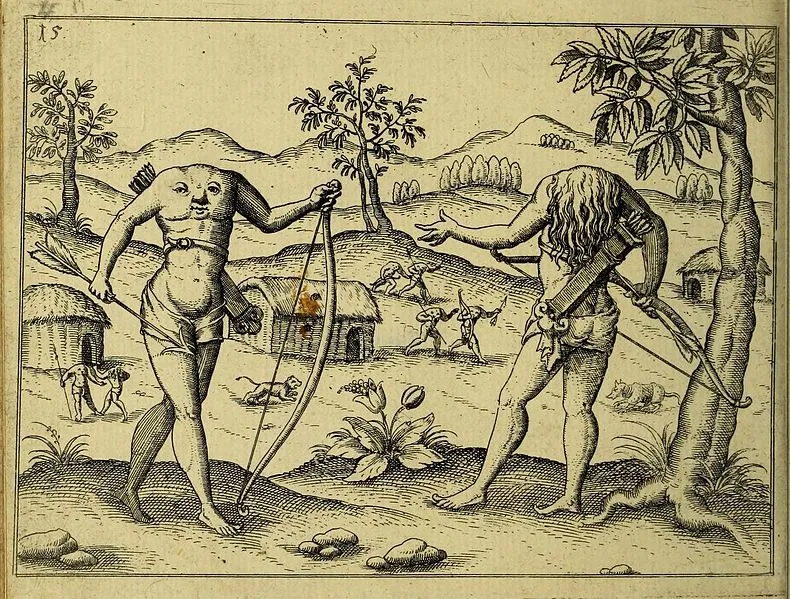

P. Gasparis Schotti Physica curiosa, sive mirabilia naturæ et artis Plate V p 451, 1662. WikiCommons.

So why did people believe these stories for so long, and where did it originate from? Numerous theories have centred on the idea that the original Blemmy warriors may have carried shields with faces on, or that they marched with their heads tucked close to their chests. Others make links with how some types of ape, such as the Bonobo, sit with their shoulders hunched up, head down, and suggest various tribes-people may have sat similarly, or that the apes themselves were the origin.

A bonobo sitting hunched over, its shoulders above its head, similar to a Blemmy. WikiCommons.

Nuremburg Chronicle, 1493. WikiCommons.

The mythology of human creatures with their faces in their chests spanned over one thousand years and found its way into many aspects of culture in the West. From adorning maps and manuscripts and churches, to being reported as scientific fact, to appearing in literature – including Shakespeare – the Blemmy fascinated Europe. They were a symbol of something “other” that could be found in the margins of the civilised world, strange creatures on the edge of truth. And even now, they continue to intrigue us today.

Previous Blog Post: A History of Food: Easter Cuisines around Europe

Previous in Mythical Creatures: A History of Dragons

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more: https://intothewonder.wordpress.com/2017/05/01/wondrous-tribes-blemmyes/

http://patagoniamonsters.blogspot.com/2012/03/sir-wlater-raleighs-blemyes.html

http://theunexplainedmysteries.com/2020/01/29/blemmyes-headless-men/

Thank you for your comment, I have left it unapproved so it stays private so I am not sure whether this comment will get back to you. Thanks for your input and glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLiked by 1 person