It is a well-rehearsed fact that in the medieval period princesses were political currency, pawns who were married off to foreign strangers as small children and were expected to fulfil their duty with grace and without complaint. But one woman who defied these expectations that we hold of medieval royalty was Isabella of Woodstock, the oldest daughter of King Edward III of England and his wife, Philippa of Hainault. She married later in life, seems to have chosen her own husband, and ultimately chose her own country over her marriage. So who exactly was Isabella?

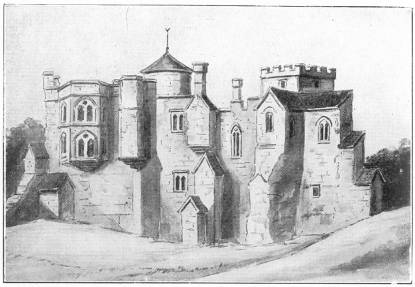

Isabella was born at the royal palace of Woodstock, Oxfordshire, in June 1332. She was the first daughter of King Edward III and Philippa of Hainault, who had married in 1328 as part of a political treaty between Edward’s mother (also named Isabella) and Philippa’s father (the Count of Hainault). Isabella was Queen of England through her marriage to Edward II, but she had launched a coup in the name of her son and deposed her husband. To help pay for the military support she needed, she obtained help from the Count of Hainault – in return agreeing to marry her son to his daughter. Although a political alliance, Edward and Philippa seem to have been very well-matched, their marriage lasting for over 40 years and producing 13 children. Isabella would grow up in a big, loving family.

As a royal princess, and the oldest daughter, Isabella was very important to Edward in forging alliances, particularly when he launched his bid for the French Crown thus starting the conflict known as the Hundred Years War. In 1335, when she was just 3 years old, she was betrothed to Pedro (later known as “The Cruel”) of Castile, the King of Castile’s oldest son. However, the marriage never came to fruition, and Isabella’s sister Joan was sent to marry Pedro instead. Sadly, fourteen-year-old Joan died of plague on the way to Castile.

As Isabella grew up, several more potential suitors were assessed to marry Isabella. In 1338 it was proposed she marry the son of the Count of Flanders, and then in 1344 a papal dispensation was sought for her to marry the heir of the Duke of Brabant. Following that, in 1349 she was offered to Charles IV of Bohemia, but nothing came of the idea. By the time she was 18 years old, then, Isabella had already gone through no fewer than 4 potential grooms.

The proposed marriage to the son of the Count of Flanders had been advanced further in 1346, after the boy had become Louis II, Count of Flanders. The guilds and townspeople of Flanders were keen for an alliance with the English king due to their interest in the wool trade, but Louis did not wish to ally himself with England, preferring an alliance with the French king. They attempted to force Louis to marry Isabella, and a formal betrothal ceremony took place in the presence of Edward, Philippa, Isabella and Louis. However, the week the marriage was due to take place Louis managed to escape his guard whilst out hawking, and he fled to the French court where he was amply rewarded by King Philip VI who promptly married him to Margaret of Brabant. Isabella had been jilted at the altar.

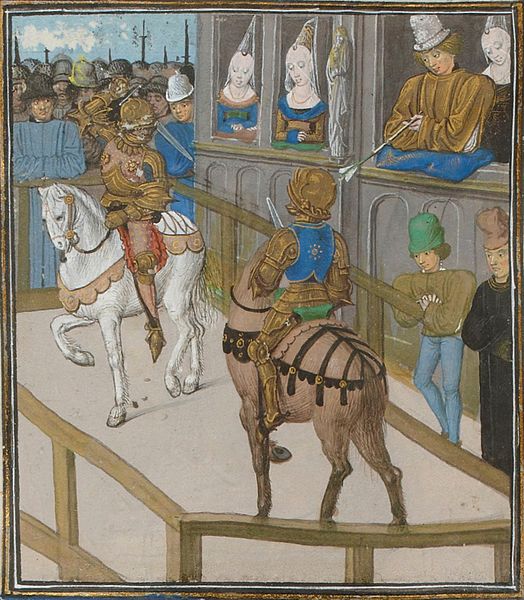

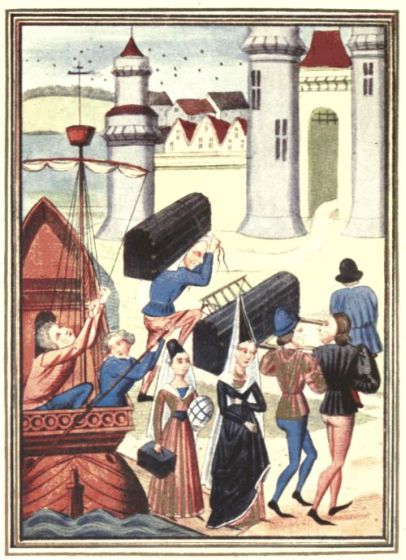

Another marriage for Isabella was proposed in 1351, to Bernard d’Albret, a Gascon nobleman, but this time it was Isabella who refused the marriage; whilst at the port ready to board the ships to take her to her new husband she refused to go, and the marriage was called off. After this time, no further marriages were planned for Isabella and she was allowed to remain at court in the care of her parents as a single woman. Her father granted her a significant income, alongside many pieces of land to support her. She was lavished with clothes and jewellery, and took part in many feasts, jousts, and celebrations at court. Whilst her younger sisters were all married off, Isabella remained the exception.

As the 1360s arrived, Isabella entered her thirties, a very late age for any noblewoman to marry. Some were even becoming grandmothers by this age. However, Isabella’s single life was about to change. In 1360, the English court received an influx of French noblemen. The French king had been captured in battle at Poitiers in 1356 and was held hostage by the English until 1360, where a deal was made that allowed him to return to France in exchange for a multitude of French nobles – and his son – being sent to England in his stead until he could raise his ransom money. One noble who was sent over was Enguerrand de Coucy, and there he remained for many years. During his time at the English court he impressed everyone with his chivalric behaviour and, it seems, he won the heart of Princess Isabella. In 1365 at Windsor Castle, Enguerrand and Isabella were married.

Enguerrand had historic claims to lands in England, which Edward duly granted him, and the couple were raised to Earl and Countess of Bedford. Enguerrand was also made a Knight of the Garter, the most prestigious honour in the kingdom, and he was granted his freedom. Not long after their wedding, the couple moved to France, returning to Enguerrand’s lands that he had been separated from for so long. The following spring, Isabella gave birth to a daughter named Marie. However, it seems that Isabella soon became homesick. Whilst most royal brides had left their home in their teens – or earlier – and so had time to assimilate to their new homeland, Isabella had married aged 33 and felt wholly English. She missed her parents and her friends and her home, and she soon returned for visits. In 1367 she gave birth to her second daughter, Philippa, in England at Eltham Palace.

A few years into their marriage, the couple hit a roadblock when the wars between England and France picked up. Enguerrand was French and held vast territories in France – but he also had lands and titles in England and, of course, was married to an English princess. His loyalties were divided and choosing a side was impossible. Enguerrand decided to create a third option for himself and went to fight in Italy for Pope Urban V instead. His conduct was viewed as exemplary and honourable by both sides, and his lands were left unharmed as the wars raged on. Isabella took the opportunity given by the absence of her husband to return once more to England.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

Over the next few years, Isabella and her husband saw very little of each other. Her daughter Philippa was betrothed aged 4 to an English noble, Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford, who was to become a great favourite of King Richard II. As her daughter Marie grew older, she stayed in France separately from her mother, as her father’s heir. The family was reunited in the early 1370s as peace once again returned between England and France, but Isabella continued to spend time in England with her husband and by herself. The couple were in England upon the death of Isabella’s father, Edward III, in 1377. With the death of Edward, to whom Enguerrand was personally loyal to, the days of Isabella’s marriage were numbered.

Enguerrand had spent much of the past decade fighting foreign wars to keep him out of the conflict between England and France, but with the death of his father-in-law, Enguerrand could no longer ignore the pressures of his French connections. He renounced his claims to his English lands and titles, resigned from his position as Knight of the Garter, and he allied himself to the French king. Noble brides of this period adopted their new countries when they married foreign grooms, and when wars broke out they remained as rulers of their adopted territories. However, Isabella had spent so long in England that she still viewed herself as English, and she had never taken up the mantle as consort of her husband’s French lands. With Enguerrand choosing France, Isabella chose her homeland, and the couple parted ways.

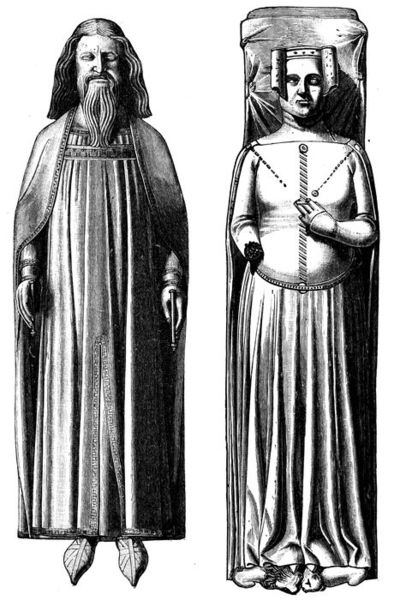

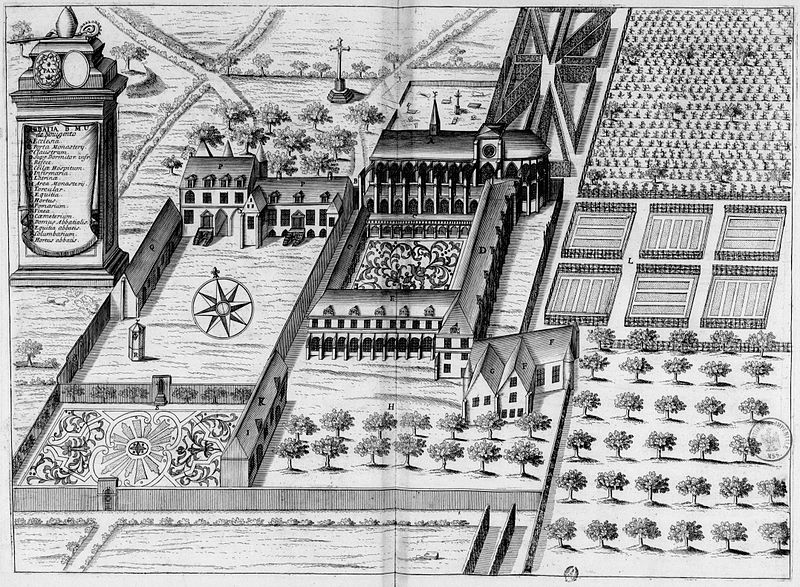

The couple stayed formally married, but Marie stayed in France with her father and Philippa was already in England with her English husband. The couple’s French lands stayed with Enguerrand, whilst Isabella gained control of their English territories. However, suspicious that Enguerrand could try to levy the income from these English lands, Isabella was not allowed direct control of her properties and they were instead placed in trust to a group of men to manage on her behalf. Isabella stayed in England for the rest of her life, and was a strong presence at the court of her nephew, Richard II. Isabella died in October 1382, aged 50, and was buried at Greyfriars Church in London. Enguerrand seems to have continued to care for Isabella throughout his life, despite their separation. He did not remarry for several years after her death, and when he created his tomb at the Abbey of Nogent-sous-Coucy 11 years after Isabella’s death, he placed an effigy of Isabella next to his own.

Isabella was a remarkable royal princess for her time. After many failed betrothals she lived for years as a single woman with her own income and lands, enjoying the festivities and luxuries of her parents’ court. She finally married later in life for love, although she could never lose her homesickness for England. The ravages of the Hundred Years War eventually ended her marriage, but she continued to live the life of a royal until her death. Although her daughter Philippa died without children, through her daughter Marie she was an ancestor of Mary, Queen of Scots, and King Henry IV of France. Isabella paved her own path at a time when women, even of royal birth, often had little choice in their lives, making her a remarkable princess indeed.

Previous Blog Post: From Olmecs to Cadbury: A History of Chocolate

Previous in Royal People: Empress Hermine: A Quotation Mark Empress

You may be interested in: Royal People: Isabella of France, “She-Wolf of England”

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-14485?rskey=AzjgFf&result=1

https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-53074?rskey=RMs4Wd&result=1

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044005602743&view=1up&seq=13&skin=2021

Fourteenth century England vol VI – “Isabella de Coucy, daughter of Edward III: The exception who proves the rule” Jessica Lutkin

2 thoughts on “Royal People: Isabella of Woodstock, The Medieval Princess Who Controlled Her Own Fate”