Today I am off on another holiday, this time to Dublin, and so I thought I needed to do something Dublin themed. I decided to write about the Book of Kells, which I am looking forwards to seeing on my visit. Due to time limitations (I am leaving in a few hours!) and because the manuscript is so beautiful, this post will be more picture based than usual, but hopefully you enjoy the change! (All images from WikiCommons)

Folio 309r – text from the Gospel of John.

The Book of Kells is believed to have been created c. 800, and is a Latin Gospel which is beautifully illuminated. Also known as the Book of Columba, it is believed that it was created either in a Columban monastery in Ireland, or had various contributions from Columban institutions in Ireland and Britain. The Book of Kells is part of the Insular Style, which is a style of manuscripts produced between the late sixth and early ninth centuries in monasteries in Ireland, Scotland and England. The style is generally considered as a mix between Celtic and Anglo-Saxon styles, with a heavy focus on intricate and dense decoration, the use of knots, spirals, and other geometric patterns. It also uses lots of animal illustrations, taken from Germanic culture.

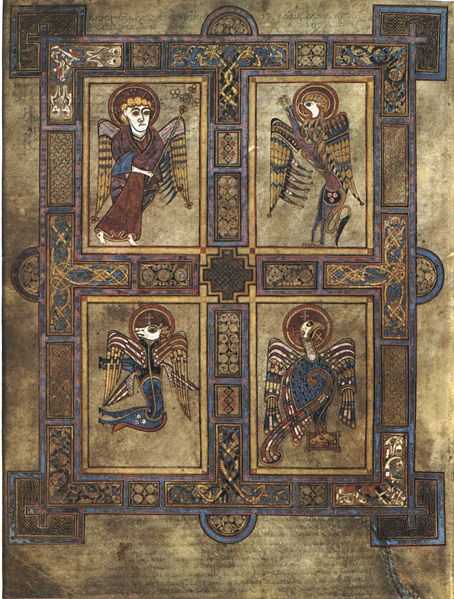

Folio 27v – the symbols of the Four Evangelists (Clockwise from top left): a man (Matthew), a lion (Mark), an eagle (John) and an ox (Luke).

The Book of Kells got its name because for most of the medieval period the book was kept at the Abbey of Kells in County Meath. According to tradition, St Columba himself created the work, although he died in 597 and the style does not match that time period. It has generally been agreed that the book was created c 800, possibly coinciding with the 200th anniversary of St Columba’s death which is perhaps the reason his name is lent to the work. This dating is around the same time that Viking raids in Iona began, which dispersed monks and holy relics across Ireland and Scotland. This then matches with the most commonly agreed upon origin for the creation of the book; that the book was created at Iona, then brought to Kells for the illuminations to be added.

Folio 292r – the page that opens the Gospel of John.

The survival of the Book of Kells to modern times is remarkable. Kells Abbey was plundered and pillaged by the Vikings many times in the tenth century and yet it is believed that the book was at the abbey during this period. In 1007, the Annals of Ulster record that the Gospel was stolen from the church. This places the book there definitively in 1007, but it was likely there for a substantial time before then for thieves to learn of its location. Luckily the book was recovered a few months later with the gold, bejewelled cover having been ripped off, taking some of the pages with it.

Here is a decorated initial – the Book of Kells is not only decorated with huge illustrations, but lots of little ones all across the text too.

In the twelfth century the Abbey was dissolved after ecclesiastical reforms, but the Gospel remained at Kells in the converted abbey church which had been transformed into a parish church. In the same century, the writer Gerald of Wales described seeing what has been assumed to be the Book of Kells, describing its beauty with such praise, claiming “You will make out intricacies, so delicate and so subtle, so full of knots and links, with colours so fresh and vivid, that you might say that all this were the work of an angel, and not of a man”.

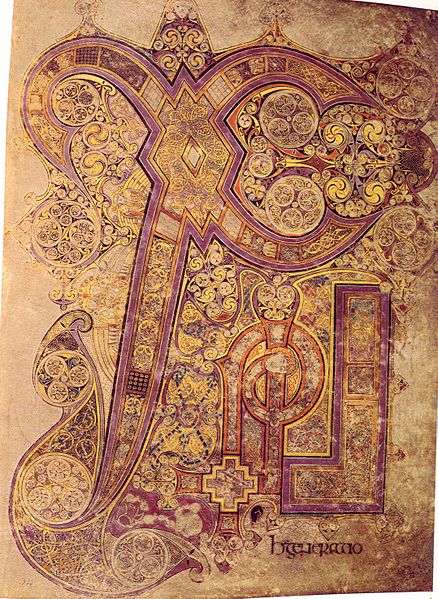

Folio 34r – the Chi Rho monogram. Chi and rho are the first two letters of the word Christ in Greek.

In 1654, the Gospel finally left Kells when the governor of the town sent it to Dublin for safekeeping as Cromwell’s cavalry were quartered in Kell’s church. Not only may the book have been plundered because they were soldiers, but Cromwell’s Puritan views would have disapproved of such a richly decorated manuscript and so his cavalry may have decided to destroy it on his behalf. The Book of Kells was presented to Trinity College, Dublin, in 1661 after the Restoration, and it is still there to this day.

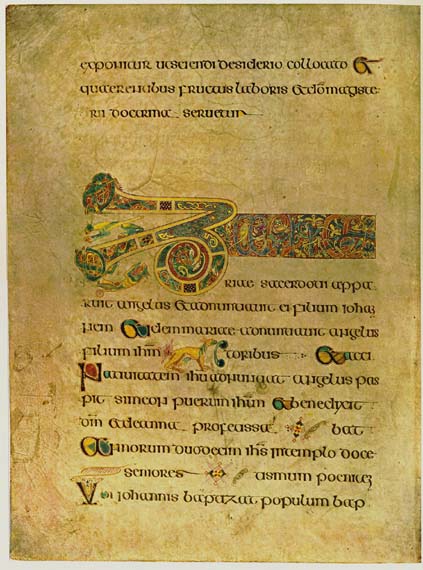

Folio 19 – the beginning of the Breves causae of Luke.

The Book holds significance through its creation and design. In the nineteenth century it was used to demonstrate Ireland’s cultural primacy as St Columba died the same year that Augustine brought Christianity and literacy to Canterbury. In the same century its rising popularity led to a Celtic Revival where designs from the book were copied and adapted, with patterns appearing in metalwork, embroidery, furniture and pottery. In line with its popularity, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were invited to sign the book in 1849. One of the folios contains an image of the Virgin and Child, which is the oldest extant image of the Virgin Mary in a Western manuscript.

Folio 7v – the Virgin and Child

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

The decorative work put into the Gospel certainly supports Gerald’s description:

“In one decoration, which occupies a one-inch square piece of a page, there are 158 complex interlacements of white ribbon with a black border on either side. Some decorations can only be fully seen with magnifying glasses, although lenses of the required power are not known to have been available until hundreds of years after the book’s completion.” [Wikipedia]

Folio 34r – small detail on the Chi Rho monogram page

The Book of Kells still has resonance today. In 2009, an animated film The Secret of Kells was made telling a fictional story of the creators of the book, who struggled to complete it whilst Vikings invaded. But beyond that, even over 1000 years later it is easy to be awestruck by its beauty. The intricate designs, beautiful colours, and the clear love of the craft that was put into its creation all contributes to a great appreciation of the work. I certainly look forwards to seeing it in person.

You can view the Book of Kells online via Trinity College’s digital collections here.

Previous Blog Post: What happened after 1066? The Harrying of the North

Previous in Miscellaneous: Magic and Robots: Medieval Automatons

You may like: World Book Day: Millennia of Firsts – a Brief History of the Book

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

I like how you refer to the creation of the book as opposed to the writing of the book. What a beautiful creation it was.

LikeLike

I saw it today – just as beautiful in person!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I must make a point of visiting when back later in the year.

LikeLiked by 1 person