When people think of medieval princesses, they often think of an almost fairy-tale like person. A beautiful young woman who was married off at a young age to a foreign prince, traded as a political pawn, with little agency of her own. Of course, this was often far from the truth, and one such example is certainly the strong-willed Anna Komnene.

Anna was born on 1st December 1083 in the Porphyra Chamber of the imperial palace of Constantinople. The Porphyra Chamber was found on one of the Palace’s terraces, and overlooked the Sea of Marmora and the Bosphorus Strait. The entire room – walls, floor, and ceiling – was completely covered in imperial purple. She was the daughter, and first-born child of the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos and his wife Irene Doukaina. The conditions of her birth to a reigning emperor in the Porphyra chamber made Anna a porphyrogenita princess, a prestigious title. From birth, Anna was destined for greatness.

Alexios I, from a Greek manuscript, and the lead seal of Irene Doukaina. Wikicommons.

As an infant, Anna was betrothed to Constantine Doukas, the son of Emperor Michael VII and Maria of Alania, and as was customary, Anna was brought up in the household of Constantine’s mother. However, Constantine died in 1095, before he and Anna were married. In 1097, Anna, who was 14 years old, married the Caesar Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger, who was 35 years old. Nikephoros was a historian, statesman, and general. Together the couple had 4 children.

Anna was not just born and bred to be a token bride, however, and she had been given an exemplary education. She was taught in astronomy, medicine, history, military affairs, geography, and maths. Anna was said to be “ardently devoted to philosophy, the queen of all sciences, and was educated in every field”. As she got older, her father built a large hospital and orphanage in Constantinople for her to administer. This was no small feat; the hospital was large enough to hold beds for 10,000 patients and orphans. Anna, being educated in medicine, taught at this and various other hospitals.

Ruins of Porphyrogenitus Palace, where Anna was born. Flickr.

Although Anna had married, she still considered the rights to her father’s throne as her own. In 1087, however, her brother John had been born, and in 1092 John was designated emperor. This caused a rift in the family, as Anna believed that as the first born, and a porphyrogenita, the throne was her right. According to Anna’s own account, upon her birth she had been presented with a crown and imperial diadem, although due to the fact that this account existed to stress her own right to the throne over her brother, it is unclear whether this really happened. Her mother, Irene, supported Anna’s claim, but despite Alexios’ love for Anna, he championed the rights of his son John. Irene continually attempted to persuade Alexios to designate Nikephoros, Anna’s husband, as the emperor instead. This would have placed Anna on the throne. Alexios did not give in, but around 1112 he fell sick with rheumatism and couldn’t move, and so gave Irene control of civil government. Finally, it was Irene’s chance to support her daughter – she gave the administration to Nikephoros.

Anna probably hoped that this would finally give her the throne, especially as Nikephoros got a taste for ruling the empire, but this was not to be. In 1118, Alexios died, and John was proclaimed emperor. It is widely believed that Anna partook in plots to overthrow or even assassinate her brother, but the plots were discovered and thwarted. Nikephoros refused to support his wife’s plans, and without this support, Anna was powerless to do much against a proclaimed emperor. She was forced to forfeit her estates, and Anna and Nikephoros retired from court. Nikephoros died in 1137, and upon his death Anna and her mother retired to the convent of Kecharitomene which had been founded by Irene several decades previously. Irene had ensured that she and female members of her family who wished to join the convent would be well provided for, giving them special quarters and superior food rations.

Once Anna retired to the convent, she devoted herself to her studies. She plunged into philosophy and history, and she held intellectual gatherings. She gained a revered status for her immense wisdom, with the Bishop of Ephesus regarding Anna as having reached “the highest summit of wisdom, both secular and divine”. It is believed she knew the Bible and Homer by heart, and it is clear she was an extremely intelligent woman. When Nikephoros had died, he was working on an essay which focused on the reign of Anna’s father, Alexios I. Not long after Anna joined the convent, she decided, at the age of 55, to complete her husband’s work as a tribute to her beloved father. Her finished work, called the Alexiad, was a history of her father’s life and reign (1081–1118). Totalling 15 volumes once completed, today the Alexiad is the main source of Byzantine political history from the end of the 11th century to the beginning of the 12th century. It gives an invaluable contemporary insight into the First Crusade, particularly from a rarely-seen Byzantine perspective. The Alexiad is also unique in that it was written by a princess about her father. It also makes Anna the only female Greek historiographer of her era.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

Anna Komnene’s exact date of death is unknown, but it is estimated to have been around 1153, making her about 70 years old at her death. From the Alexiad we can see that her last years in exile in the monastery were a cause of pain for the woman who had wished to be Empress. She wrote that no one could see her, yet many hated her. Anna had not lived the life of Empress that she had always wanted for herself, but she had been married for 40 years, had 4 children, and had gathered high esteem in the minds of many. She was one of the most educated women of her time, and was universally admired for her intelligence and wisdom. The survival of her remarkable piece of history is invaluable to us today, and gives Anna a powerful voice 900 years later. Her life may not have panned out how she hoped, but she can rest easy knowing she is still known and admired today.

Previous Blog Post: New Year, New Me: A History of Calendars

Previous in Royal People: Jadwiga of Poland

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

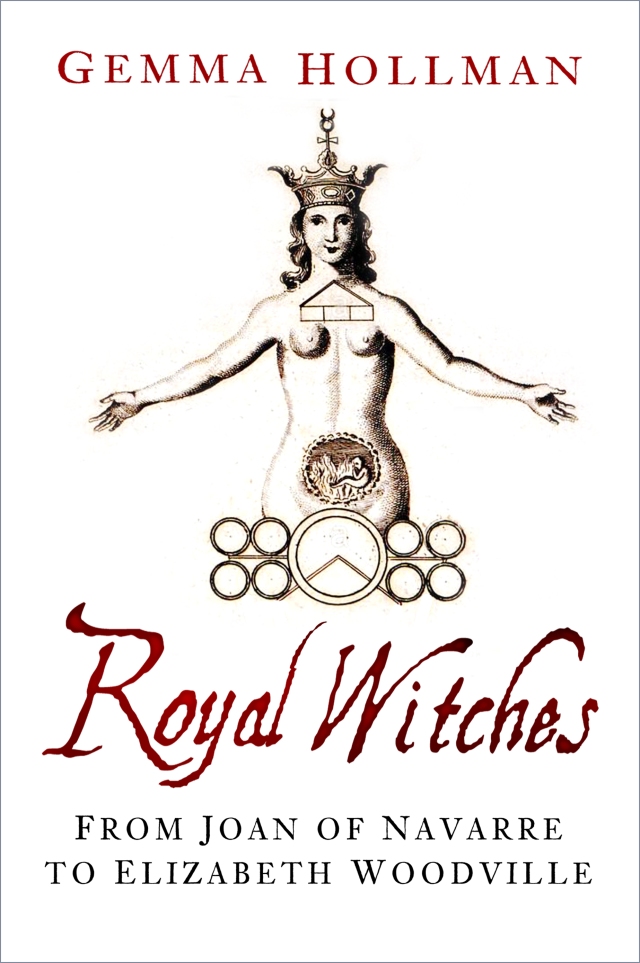

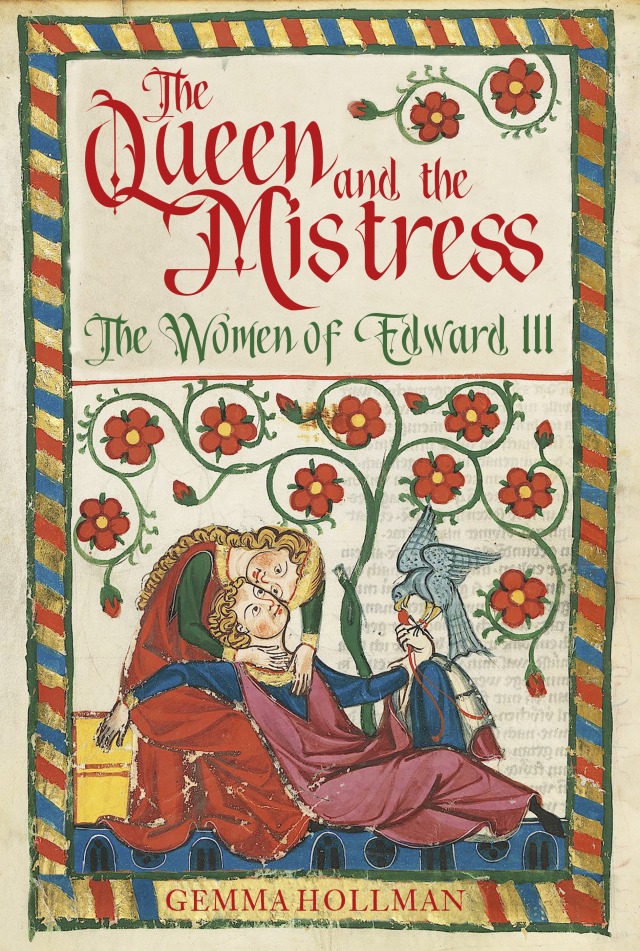

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/35510/the-alexiad/

http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190498177.001.0001/acprof-9780190498177

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Anna-Comnena

https://monasticmatrix.osu.edu/monasticon/kecharitomene

https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/anna-comnena-4635.php

http://epublications.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=jablonowski_award

Reblogged this on Lenora's Culture Center and Foray into History and commented:

Great history post. I always enjoy reading on history and learning new history posts.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Lenora's Culture Center and Foray into History and commented:

Great history post. I always enjoy reading on history and learning new history . Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike