The Early Modern witch hunts that so characterise our modern knowledge of Europe and the American Colonies, particularly in the 17th century, have captured the popular imagination for centuries. Infamous trials like that at Salem continue to lure our attention today, and our obsession with witchcraft and magic still permeates our literature, films, and television programmes. But what magic and witchcraft looked like in the medieval period is something that we don’t always give as much thought to. One of the most defining texts that influenced European thought on witchcraft was the Malleus Maleficarum, published just as the medieval period was drawing to a close. So, what was the Malleus and why was it so important?

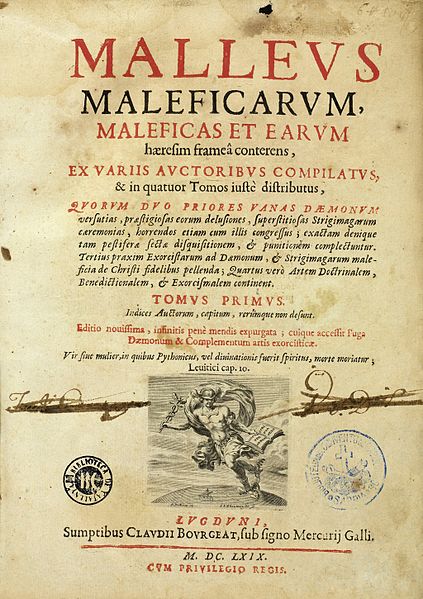

The Malleus Maleficarum was written in 1486 by Heinrich Kramer and was first published in Germany in 1487. Kramer was a Catholic clergyman who in 1474 had been appointed an Inquisitor, and his hard work had given him big recognition in the church. In 1484, Pope Innocent VIII published a papal bull which recognised the existence of witches (something which had often been debated prior to this point) and thus empowered inquisitors to prosecute alleged witches. This bull empowered Kramer in his persecution of witches, having previously been blocked in his attempts in parts of Germany.

A defining moment in Kramer’s formation of his views on witchcraft came from Innsbruck, the capital of the Austrian state of Tyrol. Here, in 1485, Kramer interrogated a woman named Helena Scheuberin and 13 other citizens who were accused of witchcraft. Kramer himself had initiated proceedings after Helena insulted him in the street when he arrived in the city. Helena had compounded this insult by disrupting, and then refusing to attend, Kramer’s sermons, and she encouraged others to miss it too. During Helena’s trial, Kramer focused heavily on Helena’s sexuality, and it was also discussed how she was an “aggressive, independent woman who was not afraid to speak her mind”.

However, at this time many places in Europe still did not consider witchcraft a serious danger, and it was often viewed as a minor offence with little to no punishment required. This was certainly the view taken by the Bishop of Brixen, Georg Golser, whose diocese covered Innsbruck. Golser disapproved of Kramer’s approach to the trial, saying that he had “presumed much that had not been proved” and eventually Helena’s lawyers managed to have the trial dismissed under procedural objections. Helena and the other accused were let free or undertook small penances. Kramer, meanwhile, continued his investigations in the town until Golser demanded he leave the city, saying that Kramer was insane and obsessed with Helena.

When Kramer left Innsbruck, he travelled to Cologne and it was here that he began work on the Malleus. His writing was very much informed by the scope of Helena’s trial. The Malleus Maleficarum is often translated as “The Hammer of Witches” and it was intended to be a treatise on witchcraft, exploring what witches were, what they were capable of, how you can identify one, and how they should be punished. The Malleus very much focused on women being the main users of witchcraft, particularly morally loose women. It also encouraged the use of torture to gain confessions, and the death penalty as a punishment for convicted witches.

Kramer said that because women were more frail and unstable than men, they were susceptible to the workings of the devil and evil spirits, whose allegiance witches required to gain their magical powers. They were also a lot more emotional and thus easier spurned to anger and eager to seek revenge. All of this meant that women were far more likely to be witches than men, an argument which would lead many future discussions of witchcraft. The Malleus detailed a huge variety of ways that magic could be used for evil, such as killing crops and livestock or bringing harmful weather conditions. A lot of the powers of witches listed were also very much skewed towards the idea of women being witches: they were also said to have sex with evil spirits, they could kill foetuses in the womb and procure miscarriages, kill small children, and cause – by illusion – the appearance of men’s penises being removed.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

Despite the later popularity of Kramer’s work, the Malleus was actually not well-received in scholarly circles upon its publication. None of the top theologians of the Inquisition at the University of Cologne endorsed the book, and they in fact condemned it for encouraging unethical and illegal procedures. Regardless, Kramer’s personal reputation was enough to sway some people to his way of thinking, and in 1491 Nuremberg council invited him to provide expertise in a witch trial they were holding. A few years later, the Master General of the Dominicans – the Order that Kramer was a monk of – invited him to Venice to give lectures on his knowledge which was attended by the local bishop. Kramer eventually won further support from the pope, being appointed a papal nuncio which was a diplomat or envoy of the Holy See.

Kramer died in 1505, but the legacy of his book far outlived him. Whilst the Inquisition did not take up the book as a manual, following the viewpoint of the scholars at Cologne, many secular courts across Europe adopted it as a guide for finding and prosecuting witches in their lands. The publication of the Malleus encouraged far more extreme punishments against witches than had been given earlier in the century or further back into the medieval period. The popularity of the Malleus as a guide is shown by the fact that between 1487 and 1600 it went through 28 editions, with 20 of the editions alone being between 1487 and 1520. That the book was published just as the printing press was created in Europe greatly helped it spread.

The Malleus Maleficarum was a very influential book written at a time when interest in witches was just starting to proliferate. The Malleus was not the only writing displaying these kinds of ideas of witchcraft, and debates about witchcraft had been growing across the 15th century in Europe. Key trials in various countries had encouraged the awareness of the evil powers that witchcraft could bestow, such as the trial against the Duchess of Gloucester in England where she was accused of using witchcraft to try and kill the King. But the Malleus certainly helped compound a lot of the emerging debates and the author’s obsession with sexually immoral women certainly helped to influence later views of witches. Its impact was clear to see for centuries to come.

Previous Blog Post: Windsor Castle, Heart of the Monarchy

Previous in Witchcraft: Royal Witches: From Joan of Navarre to Elizabeth Woodville

You may like: The Pendle Witches: ‘The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster’

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Malleus-maleficarum

https://projects.history.qmul.ac.uk/thehistorian/2020/01/24/the-malleus-maleficarum-an-earthquake-in-the-early-witch-craze/

http://www.malleusmaleficarum.org/

The Malleus Maleficarum translated and annotated by P G Maxwell-Stuart

What a great insight into the genesis of this horrible idea and the sad spurned man who wrote it. You also make a timely point about how the new medium of the printing press allowed the dangerous foolishness to reach a wide readership rather like the way ridiculous and dangerous lies are spread today by the internet.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m glad you enjoyed it! (As much as that is the right word). It can make for pretty grim reading, especially when you know what it inspired, but it is a very interesting text historically. And yes, a very good comparison! Bad ideas have always existed, but new technologies just make it easier to spread…

LikeLiked by 1 person